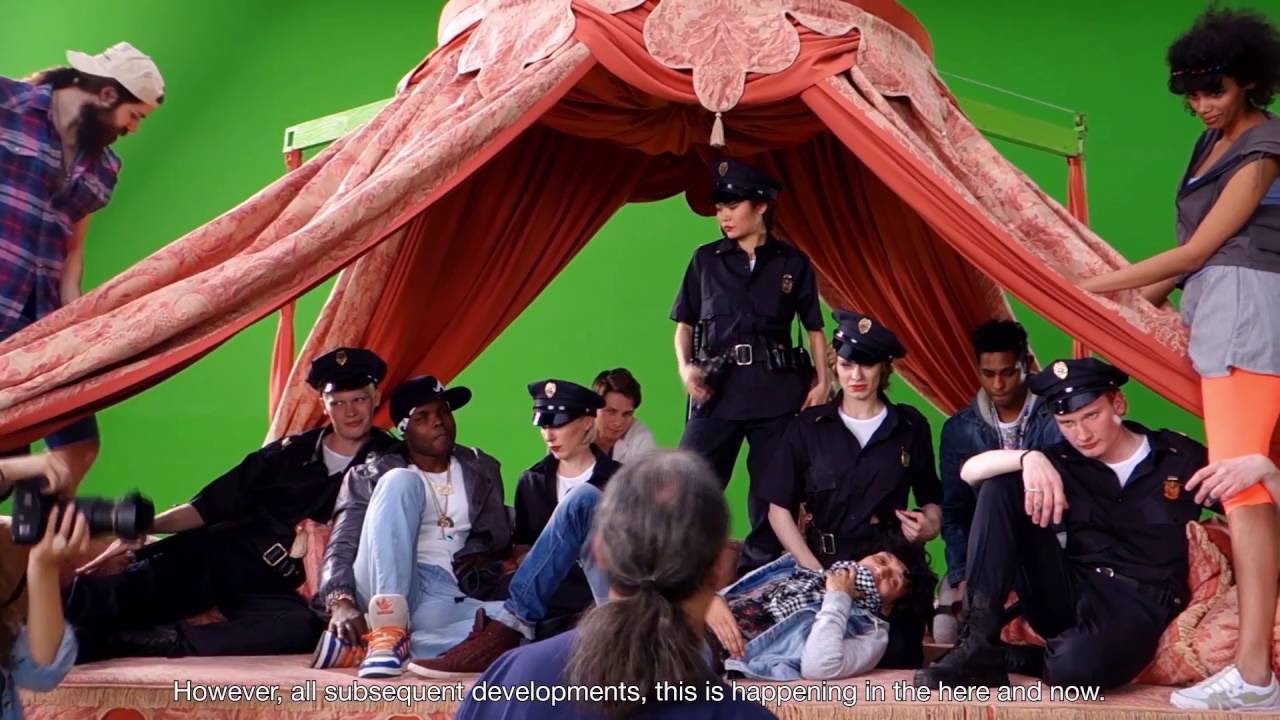

I enter the dark room, and I almost plunge into the gigantic screen where police officers are tenderly caressing civilians on a large bed that is floating amongst strange creatures. A very beautiful woman in uniform is running her hands along the body of a young, black man. A man she would have been quick to shoot, had they been in a Gotham City ghetto or Ferguson, NY. A strange dog, with octopus-like tentacles is floating in the blue sky and around the luxurious bed. I stood there, in front of this pixelated world, until some delicate microbes, gently fell down like snowflakes, on children’s cheeks. Then came the closing credits, a long list of names and characters. A man was standing in the middle of the room and with the help of the light of the screen, I recognized his face. It was then when I remembered that I was inside the Mobius art gallery, located under a sunny pavement and a hip coffee shop in Bucharest. And that in front of me, a part of Inverso Mundus had just ended – the newest artwork from the Russian collective AES+F. They say it’s a three channel video installation, but it looks like a living painting to me. That uses people and digital technology, instead of brushes.

These days, we constantly feed on images, and it’s not easy to evoke their ferocious force. The scene up on the big screen had jarred me, maybe because it’s made from the same cloth as dreams and illusions. Inverso Mundus gets its name from the Saturnalia festival, the ancient Roman holiday, where people would gather at Saturn’s temple, bring a sacrifice to the gods, and start a banquet and a carnival. The poet Catullus said that the festival was “the best of days”, when the social roles were put aside like masks, and masters would serve their slaves at the table. It took the four artists from Moscow more than a year and a half to create this piece that translates the idea behind the Saturnalia in present-day images and imaginarium. For the opening, a brigade of sewer workers are shaking pipes in slow motion; there is a petrol-like cascade of (bull) shit falling like a river, over elegant steps. A beggar hands gives charity to a suited corporate man. Men and women exchange roles. In the distance, a sinister-looking happy pig splits open a butcher. A part of these images have their roots in a series of 16th century drawings, The World Turned Upside Down. Inverso Mundus isn’t just an upside down world, but also a lyrical world, because in Italian, in verso signifies just that.

The process behind the video’s concept is long and complicated. It involves finding the right people, filming them, finding the props (in this case, a giant bed that was custom-made by Italian luxury tapestries, devices from a Berlin sex shop, and many more), followed by a long period of post-production. The last stage of the process, which discloses how much technology resembles magic, constructs the fatal weapon of seduction, the peferct illusion, up on the various-sized sreens that run continously. In the living room, or in the evening, during the news, or in the morning, at the subway, when our eyes are plastered on Facebook’s wall. After all, the Apocalypse is entertainment, say AES+F. The result of their combined work is 38 minutes of baroc hyperreality, a hypnosis that delivers you into the bowels of the world we’re all sharing. That’s why the characters are moving slowly, like ghosts or manequins; and that’s why they are so different from one another – just like a perfect ad for United Colors of Benetton.

Evgheni Svyatsky, Tatiana Arzamasova, Lev Evzovici and Vladimir Fridkes have been creating art for 30 years. In 1988, three years before the fall of the Soviet Union, they were drawing, making sketches and collages; some of which seemed to anticipate the storyboards used in video projects. What followed was photography, inside and out, filming, animation and video games. In a way, their art is also a history of all technologies that can be used to create and transform images. I talked to Evgheni, Tatiana and Lev, in the room behind the Mobius gallery, where the LED light of the computer that ran the artwork was blinking patiently. It said in big, bold letters “Do Not Touch”. Lev said, laughing “This is what makes the magic possible.”

How was it when you started out, 30 years ago?

Lev Evzovici: We started out at a time when the Soviet Union started falling apart. We had this immense void ahead of us, and a brand new world. It was such an adventure for us to figure out what we could be doing in this world, how we would create a new way of communicating with the audience. It was a blend of enthusiasm and fear.

Tatiana Arzamasova: We started out as three artists. At first, we created unique books, and then we realized that we could just create art. Out first piece was a large installation, with watercolors and embroidery; then followed all types of other works, with paintings, various objects, and photography. In 1995, Vladimir joined us and together we did Corruption Apotheosis, an installation which even though it’s made without any digital means, it looks like a horror story, such as Family Portrait in the Interior and The Prince and the Beggar. Ever since, we’ve been AES+F and we’ve been painting, sculpting, drawing, doing video and later on, we started experimenting with the digital manipulation of images.

What was the role of the artist in 80s and 90s Russia?

Evgheni Svyatsky: Being an artist in those times was highly romanticized. In Moscow, all the artists were working and there were many exhibits. At the same time, they weren’t viewed as all powerful creators, but they became mediators, who were going back to the magical roots of art. Art that wasn’t necessarily useful to living, but that could potentially influence mankind’s path. Personally, for us, what was most important was the feeling of freedom, to express ourselves and to find our own path. There was no longer the need to interact with the state, with the unions, or with the structures of contemporary art and the art market, which weren’t really present. So we needed to find a direct way to reach people. We were completely and unequivocally independent.

How did the development of the art scene change the way you work?

Evgheni Svyatsky: Everything happened very organically, because we didn’t change our ideas and our concepts at all. We use the market as a means to create larger scale, more complex projects.

Do you sell your video art?

Tatiana Arzamasova: Of course we do. It’s not just the museums that are buying it, there are also private collectors. But our art cannot compare to the painting that can hang so beautifully on the walls of a living room. When we do sell video art, we sell a light installations, meanings, colors and sounds. Frescoes that have a certain tempo that allow you to look at them in detail.

Who are your collectors?

Tatiana Arzamasova: I think they are people who find themselves in our ideas. We love art collectors, because in a way, they are very happy people. An artist can only use their own identity to complete themselves, but a collector can do it through a plethora of colors and artists. This way, their identity can be expressed through many more ways. All that thanks to money, of course. You can buy your own identity.

It’s the same for us, the ones who simply view the art. We look at it and we take whatever resonates with us. We even assume some ideas as our own. We use you, in a way.

Tatiana Arzamasova: And this happens very poetically and it’s very positive. This way, you get to share what you see and what you think.

Lev Evzovici: You can use the artists’ take on the world to express your own.

Thank you for doing the things you are doing, so we can enjoy them.

Lev Evzovici: You’re welcome (he laughs)!

If we look at these frescos in the order in which they were made, can we see our society evolving over the past few years?

Evgheni Svyatsky: Not necessarily an evolution, as we only analyze different aspects of our contemporary society. And it is, indeed, changing. For example, The Feast of Trimalchio is about the neoliberal economic growth at the start of the century. This project (Inverso Mundus) is related to the crisis that the world has been through. Other projects speak about the power of seduction of sexuality and violence, as one of the oldest structures of our language, one that has been attracting people for thousands of years.

Nearly all your works refer to other pieces from the history of art or our culture: Allegoria sacra to the Bellini’s painting of the same name, The Feast of Trimalchio to Satyricon, etc.

Lev Evzovici: For us, it’s important to understand that we belong to the same history as, let’s say, the baroque artists. And that history is not interrupted by the 20th century. We use references to mannerist paintings, the same way we use references to computer games, because they’re both a part of the same world of images.

It’s as if technology makes us believe that we’re living in a continuous present.

Evgheni Svyatsky: A present past. A continuum.

Lev Evzovici: I believe that we’re already living in the future and that the future is our present, and we can’t fear the future, because we’re living in it.

How do you think art will look like in the future, if there is a future, after all?

Lev Evzovici: I don’t know how art will look like, but in about 50 years, we’ll have the iPhone 57s, and two pills. One for becoming immortal and one for euthanasia.

Evgheni Svyatsky: To be or not to be (he laughs).

In your latest video pieces, it’s become harder to tell the difference between real and processed. But I was happy to see that you’re still working with real people, and not with CGI people, or post-people.

Lev Evzovici: Our characters are somewhere in between people and post-people. They’re somewhat zombie-like. They play the part of social robots.

It seems easy to become a social robot in our times. How can you avoid becoming one?

Lev Evzovici: You’re right, it is easy. One way to avoid this is to make an art project on social robots.

How exactly are you working with people? Do you let them improvise? Do you give them freedom?

Lev Evzovici: No, they have no freedom, whatsoever. We don’t think of them as actors.

So they’re a type of puppet?

Evgheni Svyatsky: Or robots.

Tatiana Arzamasova: They’re more likely ancient shadows in a god’s kingdom. They’re not real, they’re merely forms. They have no substance, they’re just an image.

But, these people aren’t touching each other, even though people interact with one another, and there are plenty of erotic moments.

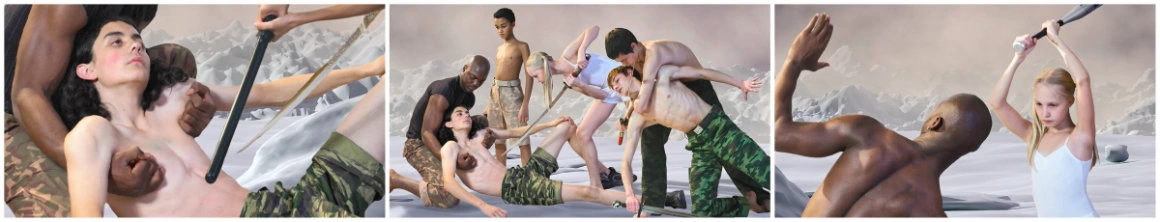

Tatiana Arzamasova: It’s not a direct action. It’s an idea of a direct action. Take for example,

Last Riot, an older piece that is full of a so-called violence, but nobody was even touching each other there. We used plenty of swords, weapons, but none of them touched the human body. There is no drop of blood, no real actor’s game.

Is the person who views your pieces a voyeur? Are they involved in what they are viewing?

Lev Evzovici: I don’t think anyone could live in those worlds, because there is no air. You can’t breathe in there. If you take a close look, you can see that these worlds don’t have a perspective, and the objects in the second plane are as clear as those in the first plane.

When you showcase your work in various corners of the world, do people identify with your art, no matter their backgrounds?

Lev Evzovici: I believe they do. Because people aren’t divided by their nationality, anymore. Rather, they’re divided inside a nation. They’re divided between smart people and dumb people, rich and poor, and so on and so forth. For example, rich people in Romania are very similar to the rich people in Moscow or Paris. And the poor people are closer not to the rich people in their own countries, but to the poor people in other countries.

I have a feeling that the distance between regular people like myself and contemporary art is on a growing trend. Because many artists and curators are adopting a complicated language, and many conceptual or abstract works become very cryptic. And if you don’t understand them, it’s your fault. It means that you’re uneducated or ignorant.

Tatiana Arzamasova: We’re trying to be transparent with everybody. With intellectuals, the art professionals, the next-door girl, who sometimes comes to our openings, all dressed up.

Lev Evzovici: Just to be clear, we’re not making any special efforts. We’re simply open.

Tatiana Arzamasova: If somebody wants to walk in, they can very well do it. There are no walls, not barbed wire. Anyone can come in and take whatever they like. It’s a type of feast. You’ve got all sorts of fruits and vegetables, foods, some of which are dangerous – you are invited to try whatever appeals to you.

So in this sense, the image plays a very important role. After a long period of time when the written word dominated, the image is starting to earn some ground. And it’s a universal language that anyone can speak, to a certain degree.

Lev Evzovici: That’s right. Right now, there is an inflation of text. When it comes to images, the more photographs are snapped by all types of devices, the harder it is to pick out the really powerful ones. We’ve got a ton of crappy images, and only a handful of really great ones.

Tatiana Arzamasova: The image has immense power in this world. If I were to paraphrase from the Bible, I would say that at the beginning, there wasn’t the word, but the image.

How did you manage to make such a critical art in Moscow, without having open conflicts with the political system?

Evgheni Svyatsky: Moscow is very different and contemporary art is highly developed. At the same time, we’re too complex for censorship and for the current political regime, which is very limited. They pick on those artists who are also political activists, it is them that they fear the most. The politics in our works are visible, but they’re making references to the entire world, not one particular situation.

There are plenty of misconceptions about Russia and I can imagine this being extended to its artists. Have you ever been labeled like that?

Tatiana Arzamasova: Of course we have. It’s good to belong to a movement, but in general, we, as artists, function extraterritorially. Society is like a herd of sheep and a pack of wolves, and artists belong to either one group or another, but they stand a bit on the outside of them. It’s there where they analyze what is happening.

Usually, visual arts are a solitary and individualistic occupation. How did you manage to work together and create such a unitary body of work?

Lev Evzovici: We’re a microsociety.

Evgheni Svyatsky: And this helped so much, especially in the 90s. We used to be quite frustrated because the society wasn’t really interested in culture. So it was very important to us to have a group of micro-references, where you could mirror yourself and be understood.

Do you have certain roles, or a hierarchy?

Tatiana Arzamasova: We all take part in the creative process and share our opinions. But of course, there isn’t a democracy. Democracy is a beautiful world, tough. Rather, we function inside an organized anarchy.

Translated from the Romanian by Cristina Costea.