I met with Romanian photojournalist Vadim Ghirda to talk about war photography. We had no choice but to talk about everything. About good and evil, disillusionment and hope, beauty and fear. About journalism and its increasingly complicated relationship with the truth, about the unsung heroes who make the work of war correspondents possible – fixers, local journalists, translators, drivers. About the baggage of suffering he has collected in the 34 years he has spent witnessing conflicts all over the world.

A relevant selection of photographs by Vadim Ghirda will be exhibited, together with images from the war in Ukraine by photographer Larisa Kalik, as part of the FRONT exhibition. The exhibition is designed by Scena9 and will open on Friday, February 23, at Rezidența9.

We met on a sunny day, at a Bucharest terrace. A bird could be heard chirping, we were drinking lemonade, and, from time to time, Vadim reminded me how lucky we both are to be here, in one piece, and how fragile our reality, which could come crashing down at any time, is.

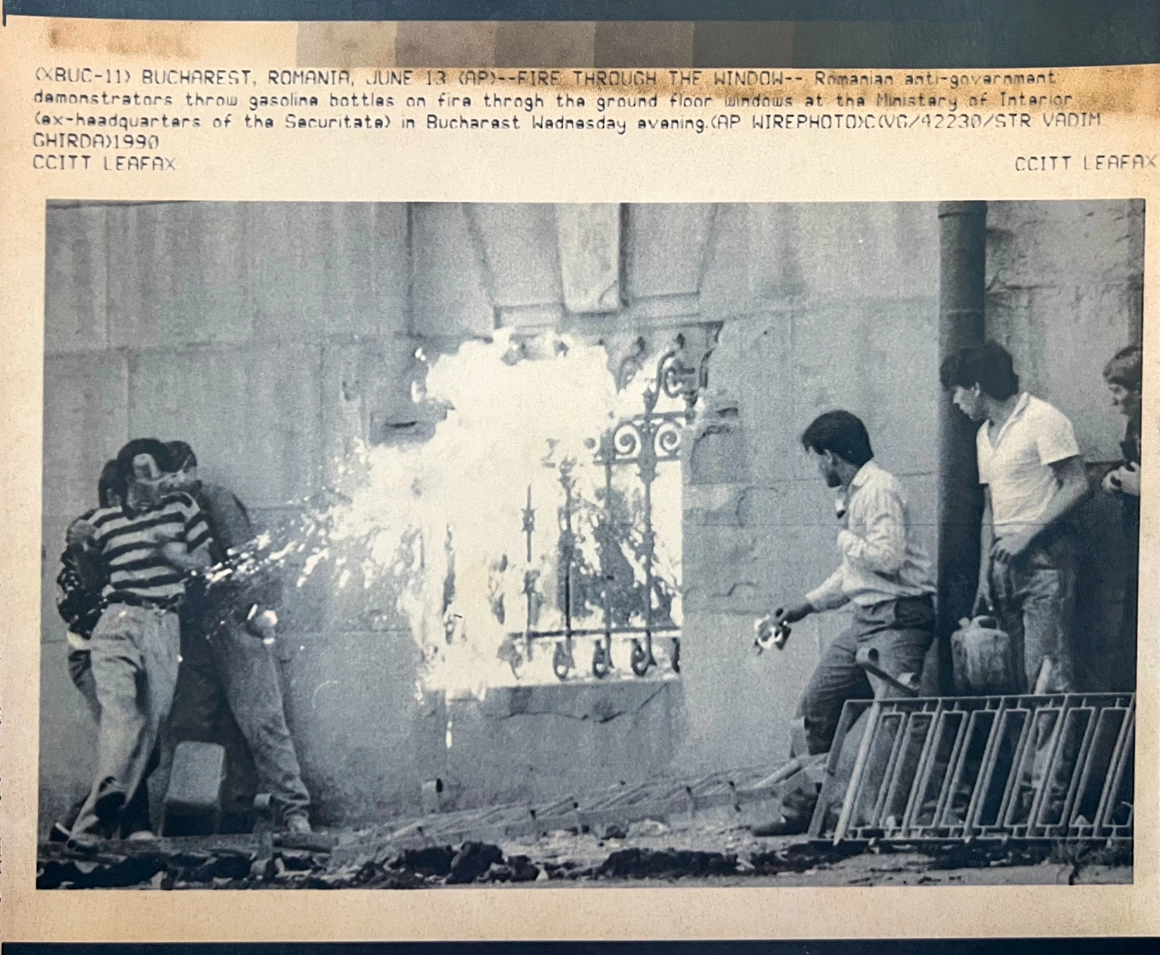

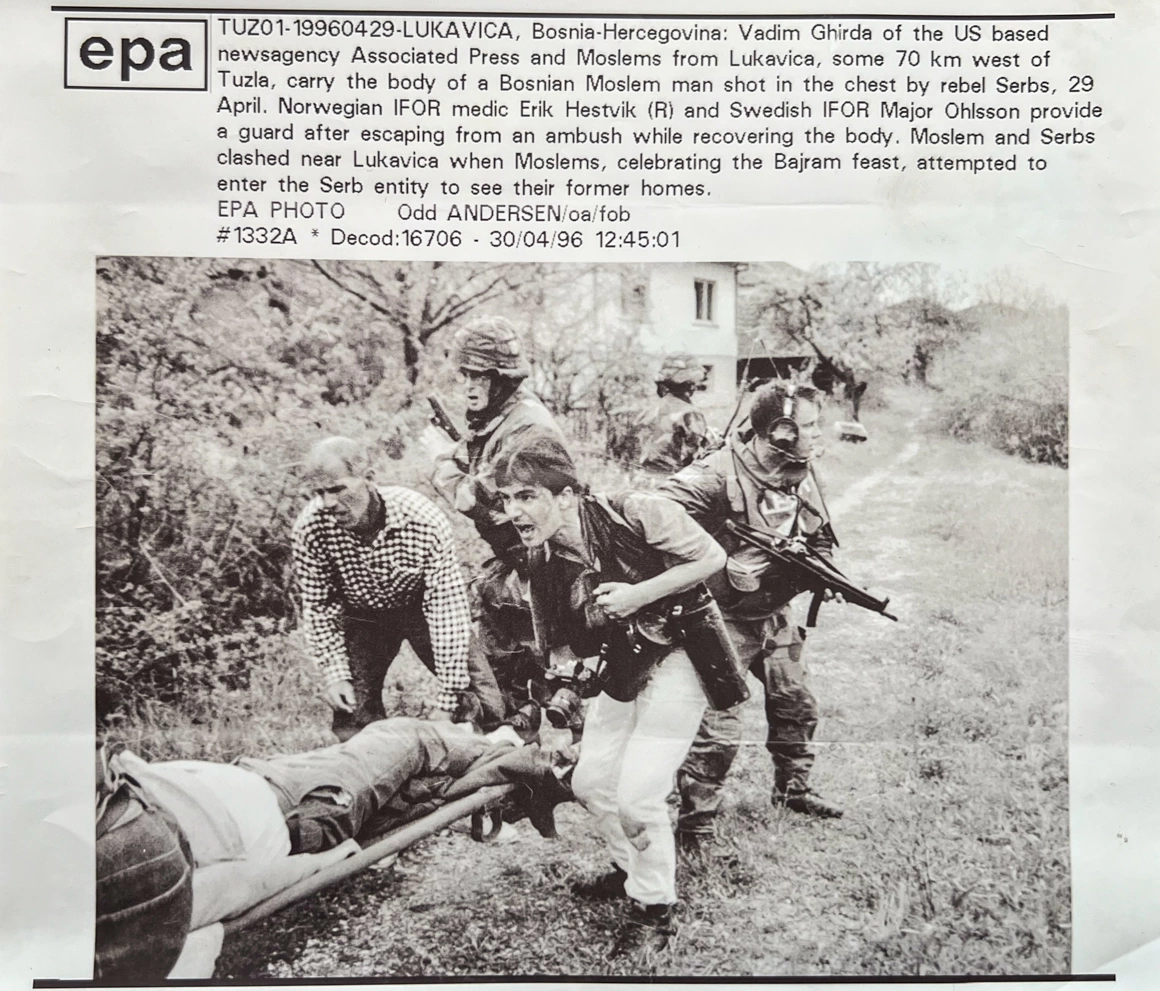

Vadim Ghirda was 19 years old in 1990, when he was hired as a photojournalist for the Associated Press (AP) agency, after documenting the miners’ riots in Bucharest. That’s when he first saw a man die beside him. That same year, loaded with photographic equipment, he boarded the train to travel to the war in the Moldovan separatist republic in Transnistria. Since then, he covered the war in Yugoslavia and all its repercussions for six years, the Israel- Palestine war, the war in Iraq and other massacres scattered across the map of the world. He has been photographing the war in Ukraine since 2014. He has won many awards for his work, including World Press Photo in 2017, the Prix Bayeux-Calvados for war correspondents in 2022, and in 2023 the Pictures of the Year International, as well as the Pulitzer for Breaking News photography, together with the AP team. Vadim's award-winning photograph shows corpses lying on the ground in a yard in the small Ukrainian town of Bucha, following a civilian massacre committed by the Russians.

When I started working in the press, also at the age of 19, it seemed to me that there was no way I would ever end up doing as good a job as the photographers I followed and worked side by side with, in the editorial office of a newspaper. We shared the tiny spaces there under the camera lenses, from behind which we would occasionally hear, „PHOTO, DOWN!”. Out of all my colleagues, most of them men, Vadim was the most intimidating. I mean, not him personally, but everything I knew about him and his work in conflict zones. When I met him, I was a little shocked, because he did not fit the war photographer stereotypes at all, something he also talks about in the interview below. He seemed very gentle, shy and modest, spoke softly, and took up very little space. Since then, he has continued to do extraordinary work with that same modesty.

In the most difficult situations, in which I would lie down on the floor and cry, he creates perfect, surgically precise, resplendent compositions.

I think it's important to have beautiful images taken in humanity's ugliest situations. As I prepared the FRONT exhibition and spent a lot of time looking at his photos, I understood that this is their superpower: through their beauty they haunt you and become impossible to ignore. They are the visual correspondent of the most disturbing act in an opera, that splendid music sung by a character who tells you that all has been lost.

Vadim Ghirda knows exactly what we are made of. He is a kind of biologist with an artist's eye, sent out into the world to find out how we, as a species, react in conditions of extreme crisis. The more I look at his photos, the more I feel that he has looked deep into us, to our essence, where all the best and worst comes out. I was very happy when he agreed to meet on a sunny day, for this long and dense dialogue, which I have edited for clarity.