Radu Jude’s latest movie, Țara moartă (The Dead Nation), screened at this year’s TIFF. It is a documentary/essay and visual and archivistic experiment about Romania in the ’30s-‘40s and about our interpretation of it, whether real or imagined. Jude’s film uses photographs from Costică Acsinte’s collection overlapped with audio fragments from the time’s archives and the harsh and resigned notes of a contemporary Jewish doctor. What transpires is the tone of an age where anti-Semitism swallowed up a whole country, chewed it up well, and spat it out, half dead, straight into communism. The following dialogue was done through email exchange, because the director is working hard on his next movie. And the photograph with the cat’s head is Radu Jude himself; he insisted I use it for this interview. It was taken by Sofia Nicolaescu, the actress from Toată lumea din familia noastră (Everybody in Our Family); she was 6 when she took it. The photo speaks a lot of Jude’s self-deprecating nature, in a world where we are used to taking each other too seriously.

What was it about Costică Acsinte’s photographs that convinced you to use them as the sole illustrations in your movie?

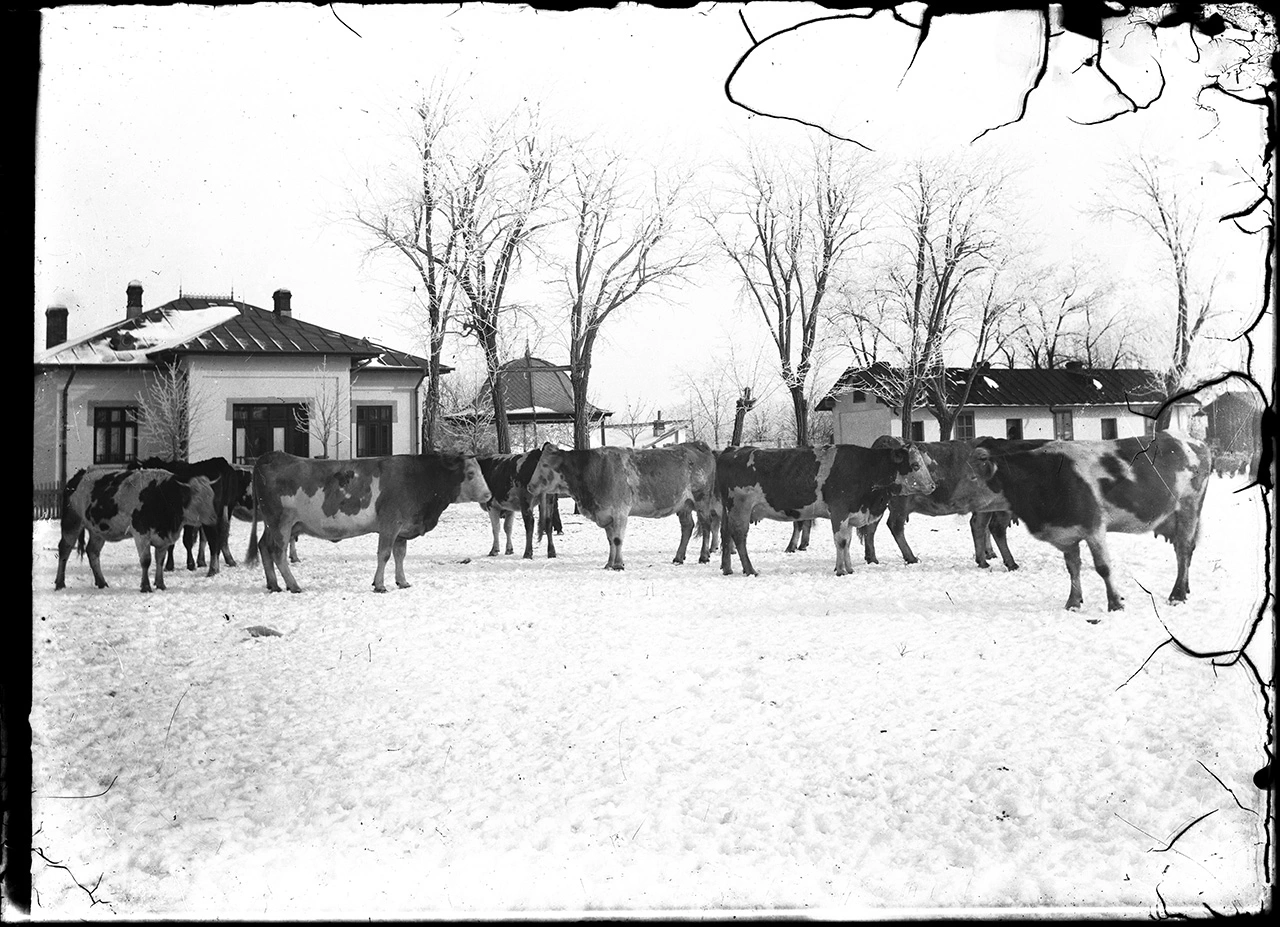

Unfortunately, this question requires quite a long answer, because it deals with the origins of this movie. The photographs were scanned by Mario-Cezar Popescu, and it’s important to remember that thanks to him, anyone can have access to this collection. I used the photos as part of my research for some of the costumes for Inimi cicatrizate, a loose adaptation after M. Blecher. I leafed through them and decided I wanted to use them in a short movie with a Chekov text (an idea that I still haven’t completely abandoned). I carefully examined the photographs and I realized how many there were. I looked at them for two weeks, while I was researching a movie project called „Îmi este indiferent dacă în istorie vom intra ca barbari” (“I don’t care if we’re going down in history as barbarians”), a movie I will be filming this summer, if all goes well. The movie deals with the crimes that took place during Ion Antonescu’s regime. And then I noticed that the things that I took place 30’s and 40’s which I found of interest were not present in this large collection of photographs. The reason is obvious: Acsinte was taking photos of the suburbs, and under very precise conditions, while all the horrors of the time were being planned or were taking place “downtown”, and only after 1942, in other various suburbs. This absence had a certain symbolism for me and I decided to change my initial project. I put Chekhov aside for a while and tried to put Acsinte’s photographs in a context that held meaning to me. As you can see in the movie, many of the glass plates Acsinte used for his photographs have the date jotted down. I started thinking that this could be a way of constructing the movie, to make a parallel between the photograph and an event that took place in Romania at that exact time. And while I was thinking about this, I found Emil Dorian’s Jurnal (Journal) in a used bookstore. I knew about it, because Jean Ancel mentioned it to me and I think Mihai Iovănel also wrote about it in his book on Sebastian. I started reading it and I was blown away by the clarity with which Dorian wrote about the time’s anti-Semitism and the massacre of the Jews by the Romanian people, especially on the Eastern Front. Dorian is otherwise a very uninteresting writer, at least from the literary critics’ perspective. So, I decided to use fragments of this Journal as a soundtrack to my movie.

While I was editing the film with Cătălin Cristuțiu, I went to the National Film Archive* to further research my new film project. I found various propagandistic movies and I thought that parts of their soundtracks could be used for my movie with Acsinte’s photographs. So, in the end, the movie is built on the parallel between these three elements: the photographs, Dorian’s text, and the Carlist, legionary, Antonescian, and communist sound bites. The photographs are in chronological order, when it was possible for the them to be dated. When it was not, the chronology was simply estimated. I don’t know how to define the movie. I avoid calling it a “documentary”, as it’s not a documentary per se, but it’s also not fiction. It’s more of a “collage film”, calling it an essay would be a tad pretentious. I think this movie works through a continuous tension between what lies in the images, and what’s outside them. During a famous conference, where Deleuze talks about Straub & Huillet’s movies and those of Marguerite Duras, he mentions this is an example of a cinematographic idea. I don’t know, it could be, I like the idea. During the public discussion that Andrei Gorzo and I had at MȚR after the screening, he mentioned Scorsese, who said something similar, that cinema means what lies inside the shot, but also outside of it. And now that we’ve mentioned Gorzo, I would also bring into discussion his study about Ujica and Farocki’s masterpiece, the Videograms of a Revolution. I think it’s very good, not because of what the movie is saying, but for what it does to the genre’s short history. Because collage films aren’t very popular, and it’s not just in Romania. It’s an almost completely ignored movie genre.

How long did it take you to select the photographs you used in the movie? And how did you put them together, like a puzzle, to triumphant legionary music, silences, official discourses, and journal fragments? The collage is at times melancholic and also extremely cruel.

As I was saying, the movie is made up of these three threads: the photographs, Dorian’s text, and the propaganda. These threads flow together in parallel, at times moving closer to or away from each other, and other times, quite rarely, overlapping. For example, when the text mentions the introduction of the roman salute, the photographs illustrate it perfectly. Most times, the viewer is asked to do a series of simultaneous tasks: analyze the photographs they’re seeing; analyze what they’re hearing on the soundtrack, make a connection, if they can, and accept that there is no connection between these elements, and that the only thing that exists is their simultaneity. It probably sounds complicated, but in reality I think it’s pretty simple. Of course you can think of a thousand ways in which this movie could have been done. (And if someone feels like it, they could very well do it themselves, why not? The photographs are available online, they’re public domain, they can be used.) Nostalgic could have been one way to go. Actually, Acsinte’s photo albums heads into that direction. In general, I’m not fond of nostalgia, especially when it comes to that time. Or maybe a more analytical direction, we could only imagine what an interesting movie Yervant Gianikian & Angela Ricci-Lucchi would make with those photos. Whatever the case, the possibilities are endless, I only chose one. For me, at least, the most important thing is to illustrate the idea that an image can’t just say something, it can also hide something that lies outside the shot. It’s a truism, naturally, but one that we usually forget when we look at a photograph.

Where does the title “Dead Country” come from? I don’t remember hearing it in the movie…

The viewers are invited to find their own meaning of the title, I wouldn’t dare take this pleasure away from them… I’m just saying that to me, it (also) represents a reference to Kantor’s show The Dead Class. Wajda beautifully filmed that great theater show.

In one and a half hours, you managed to recreate the atmosphere before the disaster, when “everybody was waiting for the fall” -, and then when disaster hit: the pogroms, the war, “the overall feeling of the hardening of the souls”, and at last what seemed like a salvation, the arrival of the soviet troops. How different is this version of the story, compared to the history presented in the school books at the moment? Or compared to the triumphant history we’re getting ready to celebrate in 2018, the Centenary of the Great Union Day.

I don’t know what the school books are saying now. Judging by what I see my eldest son learning in school, the perspective doesn’t seem to have changed much: the history of the Romanian’s people is inevitably, glorious! I think more lucidity wouldn’t hurt us. Our history undoubtedly had its glorious moments, but it is not limited to that. It’s important to remember the other moments, also. It’s an invitation to modesty.

While you were working on the movie, did you ever get the feeling that there is a connection between then and now? How far are we, actually, from the 30’s and 40’s?

//Your artistic interest tends to feature racial constructs, discrimination, and “buried giants” from recent history. Why do you find the discussion of these themes important?

Of course there are connections, but I have no idea if this actually has any meaning or not. “Importance” is a word I dislike. You could argue that something is important as easily as you would that it isn’t important. I prefer to deal with things that are of interest to me, without worrying if it is important or not.

*Radu Jude, along with nine other movie professionals, recently signed the "Arhiva de filme nu e un depozit" ("The film archive is not a storage facility") manifesto. Watch the debate on OUG 91 here and tell your friends about it. (Both links are in Romanian.)

Translated from the Romanian by Cristina Costea

For more fresh English-language cultural journalism, brought to you by the new voices of Romania, look here.