An American researcher explores the Russian and Easter European animation created during the Cold War in her new book. Little Man, main character in the films of Romanian animation artist Ion Popecu Gopo, is among her discoveries.

As a self-proclaimed animation buff, I once stumbled across an animated film that was twice voted to be the best animated film of all time, yet I had never heard of it. The film was Skazka skazok (Tale of Tales), created in 1979 by Yuri Norstein, produced at a Russian animation studio named Soyuzmultfilm. The striking beauty of every image in the film, its intimacy, and the poetic flow of the narrative captivated me. Not long afterward, my daughter came home from a thrift store with a 25 cent VHS tape that brought to my attention another Soyuzmultfilm animation. This was the 1952 film entitled Alenkiy tsvetochek (The Scarlet Flower). The film had Russian dialogue and there was only Russian text on the VHS cover, but as we watched the film, I recognized the plot of Beauty and the Beast. Again, I was struck by the artistry of the production. I was delighted by the exotic architecture and dress depicted in the story, the high production value, and beautiful visual effects of the film. Thus provoked, I looked further into the animated films from this studio and was fascinated with what I found. Then I wondered what other films I didn’t know about that came from that part of the world. I focused my investigation, defining my search parameters within Eastern Europe during the Cold War era. Everywhere I looked, I discovered an incredible wealth of animation treasures! Surely, I thought, other people from the west would want to know about these extraordinary films. This research journey ultimately resulted in my newly published book entitled Animation Behind the Iron Curtain.

My inquiry centered primarily on the animated films that children would have grown up watching and other animated films that might reveal the hearts and minds of the people of Eastern Europe. I felt that Russian animated propaganda films were already well studied and did not offer meaningful insights to the Eastern European zeitgeist. The Iron Curtain that separated our cultures for so long left us as strangers. And strangers have a tendency to distrust one another. I hoped to become better acquainted with these people so far away whose animation art had intrigued me so.

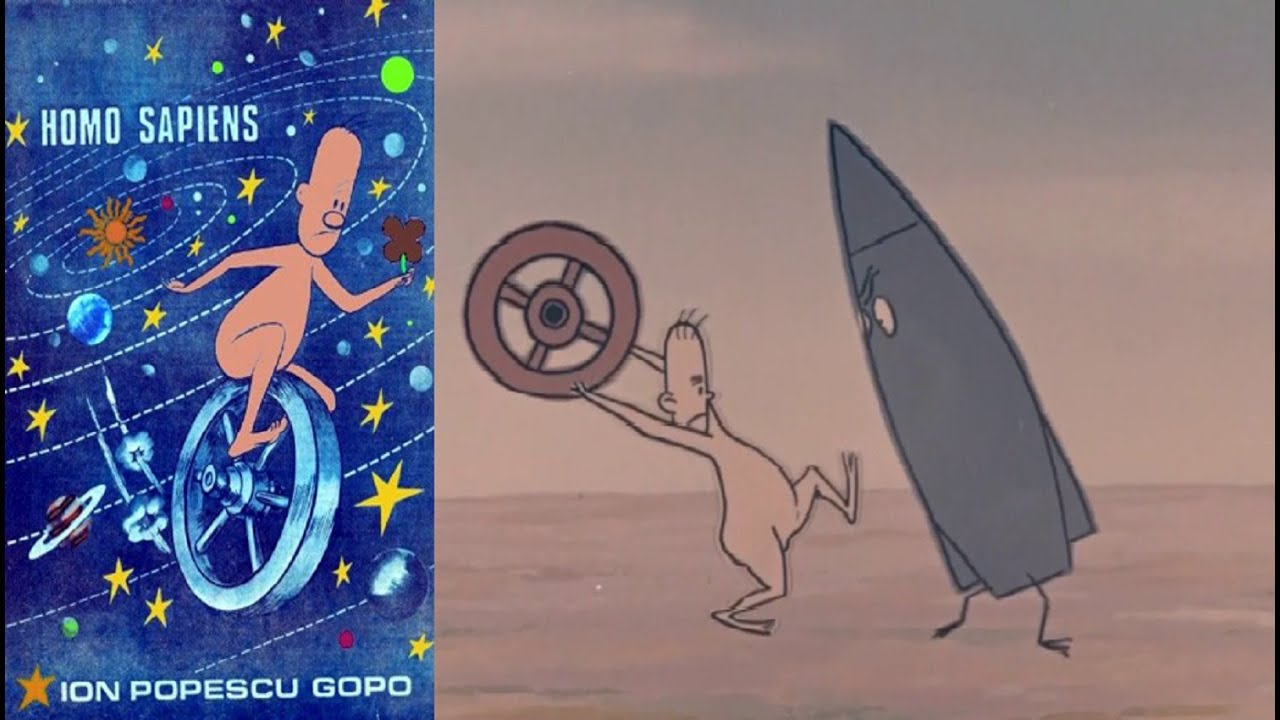

In my investigation, I learned that Cheburashka is considered the Russian Mickey Mouse and that the characters in the animated series Nu, Pogodi! (Just You Wait!) from Russia are very much like the popular American Looney Tunes cartoon characters Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner. I learned about Goodnight Cartoons, regular evening programming of animated stories that preceded the evening news for adults. I had seen some animated films from Poland with rather serious themes, but was uplifted by the Polish cartoon series for children featuring a friendly and industrious little dog, Reksio (Rex). The puppet animations from Estonia and Czechoslovakia are delightful, and I was truly charmed by the pure-of-heart Gopo’s Little Man from Romania. The creative artistry of these many films is worthy of celebration, yet these films also remind us of the many ways we, from other parts of the world, are so much alike. We all want to experience goodness and beauty, to teach our children to be kind, and to learn valuable lessons. In sharing our animated stories, we can seem less like strangers, and more like friends.

Americans are awash in our own overbearing icons of popular culture so much so that we can fail to be even aware of creative works beyond the western world (and Japan, with anime). We are missing out on some great animations! My hope is to call attention to the animation treasures I have come across in my research. These animated works of art remind us of our common humanity. They need to be preserved and their inherent wisdom appreciated across generations and cultures.

In researching for my book, I managed to obtain a travel grant to Bucharest, Romania to attend an art exhibition called The Veil of Peace hosted by Tranzit.ro. Somehow, I was on an email list that promoted the event, and when I saw that this exhibition included Romanian animated films, I quickly scrambled through my University’s grant opportunities to make the trip happen. I was having difficulty finding Romanian animations to screen online, but once in Bucharest, at the exhibition I discovered Luminiţa Cazacu’s gorgeous film, Baladă pentru o mărgică albastră, and I also visited the National Film Archive where I was able to screen complete versions of several of Ion Popesco-Gopo’s films that included Gopo’s Little Man. I was struck by the genius of Gopo’s films as he managed to encompass the history of the universe and mankind in less than 10 minutes in Scurta Istorie and likewise packaged the history of the arts in 7 Arte in the lighthearted adventures of the Little Man. Mr. Leontescu at the National Film Archive was kind enough to help me interpret some of the subtleties of Romanian humor and to appreciate the more sublime aspects of these animated gems. The trip was a great success.

I found it notable and maybe a bit ironic that as I was walking through Bucharest on my way to the art exhibition in search of Romanian animation, there were huge billboards advertising the latest Despicable Me film from America. I would have been much more interested to see advertisements promoting Romanian animation films.

The Little Man, first appearing in Scurta Istorie, carries with him a small flower, which can be seen to symbolize the spiritual sensibility of man. Shortly after the Little Man appears in the world, he notices a small flower which inspires him to sing out loud. He carries the flower with him through time and space. He nurtures the flower, planting it on the ocean floor and on faraway planets. Carrying the flower close to his heart, the Little Man embraces this flower that represents his tender soul, that most essential component of our humanity. This soul sensitivity requires care and nurturing, and it extends to the deepest realms of the ocean and far reaches of space. The soul reaches across the cosmos.

Throughout the 22 short films that feature the Little Man, he is primarily drawn without any clothing. His nudity signifies the essence of the Little Man, unadorned with trappings of civilization or culture. He is the archetypal human. His vulnerability is his strength in the power of his essential, raw, and authentic self.

The Little Man sports a perpetually neutral expression, though in 7 Arte he draws a likeness of himself on a stone wall adding a wry smile, allowing us some insight to his inner disposition. Faced with the dangers from dinosaurs, his efforts to avoid being eaten give rise to the arts. The dinosaurs express a wide range of emotions in response to the various art forms while the Little Man himself remains impassive. Naked and compelled to creative solutions for survival, this short film imparts the old adage that necessity is the mother of invention. Like the Little Man, we are equally vulnerable as we make our way through our own existence, and take the challenges of life as they come, adapting the best we can.

The Little Man is intrinsically an individual self. As such, we can view him in an existential light, where he accepts his existence at face value and creates meaning through living and nurturing his flower/tender soul. His journey through life is not generally presented in context of social relations, but he typically moves through a solitary life, even when in proximity of others. Interpersonal connection is seen in the film Alo! Halo!, where the Little Man reaches out to communicate with others, who are duplicate versions of himself. They each inhabit different areas of a planet in their solitary existence and ultimately greet one another in a spirit of friendship.

To put the Little Man in some context of Cold War Romania, the upside would be that while government support of the arts that served to meet the “collective interests” of the people was often rampant with corruption, it also allowed for state support of animation artists to create great works without condition of commercial viability. My research indicated that animation art often did not receive the same level of scrutiny and censorship from communist officials as other forms of art, and animations that included folk tales or simple fables were encouraged for their didactic qualities.

It can be difficult for Americans to understand the severe perils that Eastern Europeans faced during the Cold War years. We can learn about the history but may be challenged to relate to the trauma induced by the massive social engineering initiatives of Soviet communism. My estimation is that most Americans feel an overall sense of security within our democratic society and with a physical separation from potential external threats by oceans on our eastern and western borders, though we are more recently experiencing our own feelings of trepidation and crisis of faith in our national leadership. But even without mortal fear of a despotic government, it seems that the human condition is fraught with danger. We can all experience varying degrees of uncertainty in meeting our basic physical needs, face assorted forms of oppression, and/or balance at the edge of chasms of hopelessness.

Living through times of pervasive fear can compel us to seek out calming forces, and art can shift our focus to a different facet of our existence, to the solace of contemplation, humor, and appreciation of beauty. With this in mind, the Little man transcends the environment in which he was created. He originated in perilous times of Romanian history, but the message he imparts is timeless and has no political boundaries. We can engage in this animation art to allow ourselves a moment to shed the material and political concerns of our daily lives. The Little Man inspires us to carry on, face life with an open heart and tenderness intact. Ready to experience what life has to offer, the Little Man nurtures his delicate soul and extends it out through the cosmos. If only we could all find a way to do the same.