Sometimes, I don’t recognize my own city. I wander its streets and it seems that there’s something missing. That layer of innocence that used to permeate its streets has vanished. The sidewalk trembles under your foot, as if underneath, there is a sleeping giant who is slowing waking up from its slumber. I found out about the Iași Pogrom after I left for college in Cluj. For 18 years, nobody ever told me what happened here in 1941, not even my history teacher. The official mythology has created, for the children born and raised in Iași, a city that seems to be stuck in the middle of the 19th century. A city where Eminescu sips on wine at the Bolta Rece restaurant and Creangă shoots crows on the Copou hill. The mass killings of the summer of 1941 were erased from the collective consciousness and buried somewhere deep under the pavement of Unirii Square. But these past few years, young researchers, led by historian Adrian Cioflâncă, are looking for mass graves and personal histories, while making note of memory places and disturbing the peace of a country town. These days mark the 75th year anniversary of the Iași Pogrom, the reason why curator Olga Ștefan created Fragments of A Life / Fragmente dintr-o viață. It is an exhibition for Tranzit.ro that is trying to shake the general numbness and spark discussions about violence, displacement, immigration, identity, the home, and us versus the others. It is the first collective exhibition of contemporary art that deals with the Romanian Holocaust. You can see it in Iași, until August 30th.

“The streets were empty and terrifying. Cats and dogs were lapping up blood from puddles.” (Haim Solomon’s testimony, United States Holocaust Museum)

I discovered this quote two years ago, when I was looking for information about the Pogrom. I just can’t seem to shake the image of the animals lapping up blood from puddles, or a photograph from July 1941, of bodies laid on a sidewalk with a man passing by waving an umbrella. How can you wave an umbrella near people who have been murdered? How can you clean the sidewalk from the blood and the history from a massacre? How can you deny responsibility? How can you not understand that if you refuse to see these things, a part of your and your country’s identity is dishonest, and it will eventually turn against you?

During the interwar period, more than a third of the Iași residents (even half, according to some sources) were Jewish. From what used to be tens of thousands, there are now only a couple hundred. 13,266 Jewish people were killed during the Pogrom of June-July, 1941. It was the largest massacre in Romania’s modern history and one of the most violent pogroms in the history of the Jewish people. 13,266 people were shot on the street or at the police station, put in death trains by the police with the help of soldiers and the general population. The ferocious anti-Semitism at the time (Hannah Ardent in Eichmann la Ierusalim wrote “It’s not an exaggeration to state that Romania was one of the most anti-Semitic country in Europe, before the war”) and the war propaganda (there were rumors that the Jews showed the Bolsheviks the bombing targets; actually, it was not just a rumor, there were posters all over town that instigated to violence against the traitors) set the ground for the massacre. On June 27, 1941, a few days after Romania went to war on Germany’s side, general Antonescu made a call to Iași and ordered Colonel Constantin Lupu to clean the city of Jews. What followed were a few days in which the community took part in the killing of its members.

In 2004, the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania launched an official report that said that “the Romanian authorities are solely responsible for planning and acting out the Holocaust.” During the Holocaust that took place on territories that were controlled by the Romanian state, between 280,000 and 380,000 Romanian and Ukraine Jews died, while 25,000 Romani people were deported in Transnistria.

In 2013, a poll by the National Council for the Prevention of Discrimination and IRES asked, among other questions, who is responsible for the Holocaust in Romania. 69% of the respondents said that it was the Nazi Germany, 22% responded that it was the Antonescu government, 14%, the Soviet Union, 8% believed that the Romanian people were responsible and 6% blamed the Jewish people themselves. Almost half of the respondents said that they wouldn’t like to be friends with Hungarians, Romani or Jewish people.

I’m sitting down with Olga Ștefan in a garden on Lăpușneanu Street, right next to the newly opened space of Tranzit.ro in Iași. The gallery is tiny, just big enough to house a few dozen people. It is inside a house that is also part of history: Goldstein Heinrich was taken from there to forced labor in Măcin. It is the end of June and the official commemorations begin – it has been 75 years since the Iași Pogrom, from June 27-29, 1941. Olga Ștefan is the curator of the Fragments of A Life exhibition; she came to Iași for the duration of the exhibition, and for a series of events that are part of the exhibition – screenings, debates, and a theater play. Olga left Romania with her family in 1983, lived for 26 years in Chicago and now she lives in Zürich. She is the niece of the Romanian dissident, Gheorghe Ursu. She speaks Romanian with a thick accent and looks for the equivalents of words in her mind – fittingly, she mixes displacement with the Romanian word. I listen to her talk about the exhibition and I can’t help but think that sometimes it takes an outsider to raise questions about the life and history of a community. Although, to be honest, Olga isn’t really an outsider. Her grandfather died in one of the death trains during the days of the Pogrom. The artists that she featured in the exhibition also have roots in Iași and in Romania and their lives have also been deeply affected by the displacement. Their identities have been broken and the stories of their families have broken into pieces scattered on many continents, to the point that the personal history has become as hard to put back together, as the larger and official history. But, according to the curator, we don’t have a shot at connecting to the larger history, without the help of smaller, and more personal histories.

I listen to Olga: “Everybody says that it is a delicate subject. It’s more than obvious that it is a delicate subject, but for whom? And why do they think it’s so delicate? Delicacy is a way of saying We don’t really want to talk about this and we don’t want it to be made public. It’s not really something that has been brought to public awareness. Not artistically, anyway. There have been commemorations, even now, at the same time that our exhibition is happening, there is the official commemoration that is organized by the “Elie Wiesel” Institute. So, in a way, there are public conversations, but only then, during that event. The discussion needs to be integrated in the city’s conversation with the collective history. What does commemoration really mean? It’s not something that lasts for 3 days and then it is swiftly forgotten. I, for one, am trying to find a way to enter the city’s conscience and to resuscitate a history we no longer see. Even here, everything is paved and looks pretty, but what lies underneath needs to be brought into conversation once more, so that it stays in our conscience forever. And I’m not just referring to the Pogrom, but the entire Jewish life, that used to make up to half of this city. It used to be a half and half city. Now, there’s nothing. The question here is how to make ourselves aware of this past and how to bring it back to life for the public. ”

Alright, but why now? “There are very few people from that generation who are still alive. It is the right time to bring the conversation back. This past scattered families across the world and we’re seeing the same thing happening all over again, right before our eyes. We’re living another large crisis and displacement. What are the ins and outs that cause these people to become displaced? They, themselves are going through some major displacements. I thought it was important to make these connections. It was a very important subject to start digging into.”

How did she dig? “Not with a shovel (she laughs), even though that would have helped. I dug around by doing research, I read all sorts of books, writings, artists, who were originally born here, in Iași, and for whom this event was the key moment that changed the trajectory of their destiny and their lives.”

The artists Olga selected come from different generations. Samy Briss was born in Iași, in 1930. He went through the horrors of the Pogrom and immigrated to Israel in 1959. He’s the author of the series, Iași, zile negre (Iași, Dark Days), one of the first artworks about the days of June, 1941. He did the artwork in 1948, when he was 18. The disfigured face of a little girl who is looking at something sticks with you.

Elianna Renner is a concept artist from Switzerland. She was born there in 1977 and lives in Germany. Her great-grandfathers, Yankl Wasserman and Yankl Solomon, left for the market during the Pogrom and never came back. The artist has been trying to put together their story by talking to many family members, scattered all over the world. The result is a video of parallel tracks and different versions of the story. It is as if you can almost see the memory in action.

Daniel Spoerri is an important sculptor, performance artist, and Swiss writer. He was born in Galați, in 1930. His father died, same as Olga’s great-grandfather, inside one of Iași’s death trains. On display there is an hour-long interview with Spoerri (about the journey to Romania in 2010, in his father’s footsteps; about what it means to belong to a place; about life and death) and a photograph – the image of a 17th century coin showing a Jewish person converting to Christianity.

When it comes to Romania’s younger generation, Olga collaborated with Adi Bulboacă and Gabi Basalici for two of the clips presented in the exhibition. David Schwartz, Alice Monica Marinescu, Ioana Florea and Katia Pascariu came to Iași cu Între granițe (Between Borders), a debate-performance that I personally missed, because I had to leave town. But we’ll get to all see it in November, at Macaz in Bucharest.

Olga herself is part of the exhibition, with a clip made form Skype and face to face conversations with her grandmother, who lives in Chicago. Olga’s grandmother is Sorana Ursu, the wife of dissident Gheorghe Ursu, killed by the communists, and also the daughter of Isac Ușieru, killed during the Pogrom. Interviewed by Olga, Sorana Ursu remembers how she lived through the day of June 27, 1941; how they came to take her father and how she went to search for him in the city. How her father was let go, but she advised him not to hide anymore. How they took him again and he never returned. “I always thought, said Sorana Ursu, that Jewish people and the Romanians have a lot in common. Both need to find an identity…”

“But, Olga tells me, there is this whole idea of the disappearing memory and how nothing is concrete and touchable. When we try to invent the personal past, it’s more than obvious that we’re inventing our life, by talking about it. And that, in fact, things that have happened in our lives aren’t all that clear, either. What is there left to say when we’re trying to rebuild the lives of others, who have been gone for 3 or 4 generations? This is what’s it’s about, this phenomenon of trying to rebuild what happened. Who were those people? Who are we? Where do we come from? On what are we built? How does a city remember its own past? ”

“How does a city remember its own past?” I ask. “It doesn’t. It remembers what it likes to remembers. I heard Adrian Cioflâncă talk about his years spent at the faculty of history and about how he wasn’t told anything about the Romanian Holocaust.”

On June 29, Adrian Cioflâncă, director of the Center for Jewish Studies in Romania, attended a short conference during the series of events that Olga organized. He talked about the recent project of recovering the biographies of the Pogrom victims. And about the work needed to uncover not just the biographies, but also the bones, through the identification of the mass graves in Moldova. A mass grave put a new massacre on the map. A slide from Cioflâncă’s PowerPoint lists all the massacre spots from ’40 to’41: Galați, Dorohoi, București, Stânca Roznovanu, Vulturi Forest, Iași, Gura Căinari, Huși. Near many of the small train stops from Bucharest to Iași, there are mass graves of the death trains victims. They are not marked, you can’t know they are there. But they are there.

The day I was writing this piece, Cioflâncă announced the discovery of a new mass grave in the Vulturi forest. The authors of the massacre are Romanian military from the 6th Hunter Regiment. Also from Cioflâncă, I know that the Iași Pogrom was one of the most visually-documented pogroms in the world. This means that a plethora of photographs were taken. A lot of them are circulating liberally on eBay and are sold starting from tens to hundreds of Euros. You pay up and get yourself a piece of history. You don’t pay, you don’t get yourself a piece of history.

Adrian Cioflâncă says that he received death threats since he became a sort of public defender for the recovery of fragments of a history that is less than comfortable. I ask Olga if she is afraid of violent reactions at the exhibition. She says she is not. But, “I was shown an antique store down the street and it would appear that the man there is quite intransigent. I heard many stories from people featured in the exhibitions who have gone inside his store to see what it is that he is collecting. He’s not collecting anything, he just wants to control the narrative, by removing images from the public space. Someone entered his store and he reacted with “What? Are you a Jew, is that why you came here?” The antique store is on the other end of the street and the antiquarian is a type of pillar of Iași’s micro-society of collectors. He’s also maybe the most often-talked about local character in the city’s school magazines. He tells the children about his rare manuscripts and about his passion for the old city of Iași. On the same street, two versions of the truth. In the same city, two overlapped layers of history. On the sidewalk where a family with children was shot, people are walking past the Ozone clothes store. Asked (by Romulus Balazs, the author of the Souvenirs de Iași (Iași Souvenirs) documentary, which is part of the exhibition) if he were willing to put up a memorial stone, the antiquarian said that he wouldn’t and that he doesn’t really understand what this whole thing is about.

Nothing remains the same, we’re reinventing our own history every single day. We, the Romanians, have always been at the mercy of someone else; we, the Romanians, have always been oppressed; we, the Romanians, haven’t done anything bad, others have done bad things to us; we, the Romanians, have stopped the barbarians from advancing into Europe. We, the Romanians.

In March, President Iohannis paid a visit to the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. He stated that he supported the creation of a Jewish and Holocaust museum in Romania and that of a regional center “that deals with assuming our own past”. Quite a massive undertaking. Iași’s liberals swiftly took over this idea and asked for the museum be located in Iași. As a sign of redemption and to encourage tourism: “We have the Tarom flight from Iași to Tel Aviv and come fall, Wizz Air will also have a flight route between the two cities” said Marius Bodea, PNL Iași leader. For now, there are a few plaques, placed under the recommendation of the “Elie Wiesel” Institute, anad the online museum, also created by Cioflâncă’s team. Last but not least, there is the must-visit Fragments of A Life exhibition on Lăpușneanu Street, until the end of August. For now, the organizers estimate that around 300 people have visited it. But the sleeping giant doesn’t awake form its slumber that easily*.

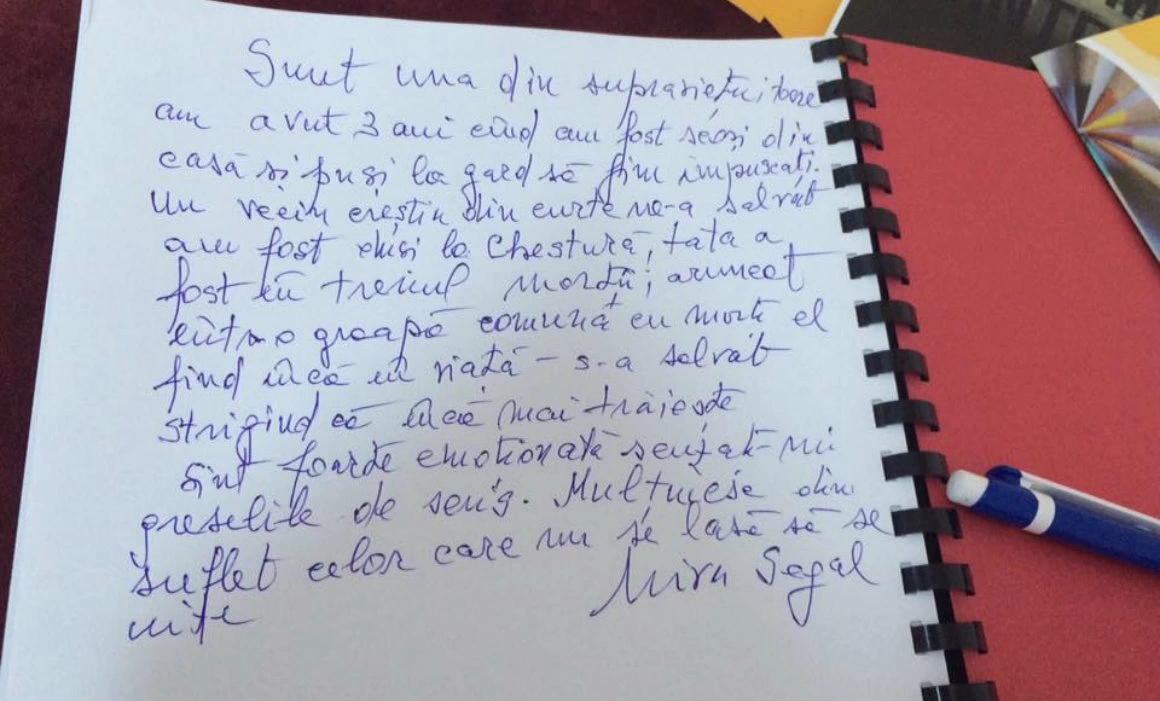

This is what someone wrote in the guestbook of the exhibition that commemorates Iași’s Pogrom.

“I am one of the survivors. I was three when they took us out from our home and put us against the wall to be shot. A Christian neighbor saved us. We were taken to the police station; my father was inside a death train; he was thrown alive inside a mass grave. He saved himself by screaming that he was still alive. I am very emotional, please forgive any mistakes I make. From the bottom of my heart, I want to thank those who are not allowing this to be forgotten. Mira Segal”

* I borrowed the sleeping giant metaphor from an interview with Kazuo Ishiguro. He said that every country has its giant buried deep in a forbidden history. The pogrom is Iași’s giant.

** The project Fragments from A Life is curated by the 1+1 Association, co-curated by transit.ro/Iași, and co-financed by the National Commission of Cultural Heritage

** In case you want to read more about this, we recommend:

- Aliyah Dada, d. Oana Giurgiu, a well-documented history of Jews in Romania

- Valea Plângerii (Valley of Weeping), d. Mihai Leaha, a documentary about the deportation of the Romani people to Transnistria

- Groapa comună (Mass Grave), by Philip Ó Ceallaigh, a piece from Decât o revistă about how you can literally dig up history

- On Dela0.ro you can find articles from 2010 onwards, about the Romanian Holocaust

- Ultima țigară a lui Fondane (Fondane’s Last Cigarette) and America de peste pogrom (America After the Pogrom), by Cătălin Mihuleac

- Radu Jude’s newest film, based on Inimi cicatrizate (Scared Hearts), by M. Blecher

- „Ce face Mihail Sebastian în Marea Britanie”(What is Mihail Sebastian Doing in the United Kingdom?)

Translated from the Romanian by Cristina Costea