We talked to actress Ilinca Manolache about theater and its limits, Love Island, society and TikTok, misogyny and trivialized violence, as well as her role in Radu Jude’s latest film, “Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World”.

Ilinca Manolache blows a bubblegum balloon on the cover of Cinema Scope magazine. She wears a glam gangsta sequin dress, scattering light like a disco ball inside a car. The image's texture is grainy, and she is tough and exhausted, pissed and polished, as in a feminist poem. Ilinca Manolache applies a TikTok filter effect. She turns into a bald man, sporting a unibrow and goatee, spurting delirious insults at women as if on an East European construction site. Whether at home, in his car, alone or with others, he is Bobiță – a performative gesture recycling the vicious language thrown daily at women, hoping to defuse it through confrontation and humor.

Ilinca Manolache is an actress and performer. She is 38, and for the past 15 years, she’s been employed at Teatrul Mic in Bucharest, as well as a loyal presence on the independent theater scene. These days, she’s performing at Teatrul Act in the production Sunline, directed by Radu Iacoban. Her character shrieks and hollers from the top of her lungs, once more in a glittering silver dress, once more a woman pushed to her limits. Recently, she had her first leading role in cinema. An eclectic and electrifying film, spurring loads of laughter, albeit uncomfortable ones. A wild, brainy, punk movie, a meta creature growing multiple heads, each of them turning towards a different era of audiovisual history. It suited Ilinca like a glove.

In the film, the actress plays Angela Răducanu, an exhausted and exploited, audacious and sexy production assistant, squashing herself through the Bucharestian chaos in search of casting for an Austrian corporate work safety video. Angela works, screws and sleeps in the car’s tight confines, in long and repetitive shots turning her performance into an impressive tour de force. She crosses a city as an incoherent blob of concrete, its inner beat but a low-brow brew of local trap, techno, and punk references – from Macanache and Gheboasă to Sex Pula Pistol, the film is an ode to the city pushed from the ghetto to its corporate aquariums.

Neither in content nor form is Radu Jude a compliant filmmaker playing it safe. Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World is a quirky film dialogue, a play of mirrors reflecting upon each other until they shatter. Entangled in the director’s tapestry of glitches is a spectrum of images. Some are shots from Angela Goes On – the 1981 drama directed by Lucian Bratu that captures the everyday life of a woman taxi driver in communist Bucharest. Others are renderings of Bobiță – the online feminist performance put together by Ilinca Manolache and Ruxandra Maniu during the pandemic. They invite women to turn into misogynistic digital morons using online filter effects of beards, bald heads, mustaches, and alpha male scars. It's a "critique through extreme caricature," Angela labels it in the film – one that finds an unexpected place in the gritty-glittering aesthetic of capital city traffic jams. The monobrow and goatee filter, the string of burlesque and bizarre insults turn Angela into an "Alice in Horrorland," as the French publication Libération calls her, and Ilinca Manolache into the "blonde fury" deserving the "Palme d'Or for the most chaotic actress."

In the Bucharest chaos we find each other as well.

"A formidable whorehouse"

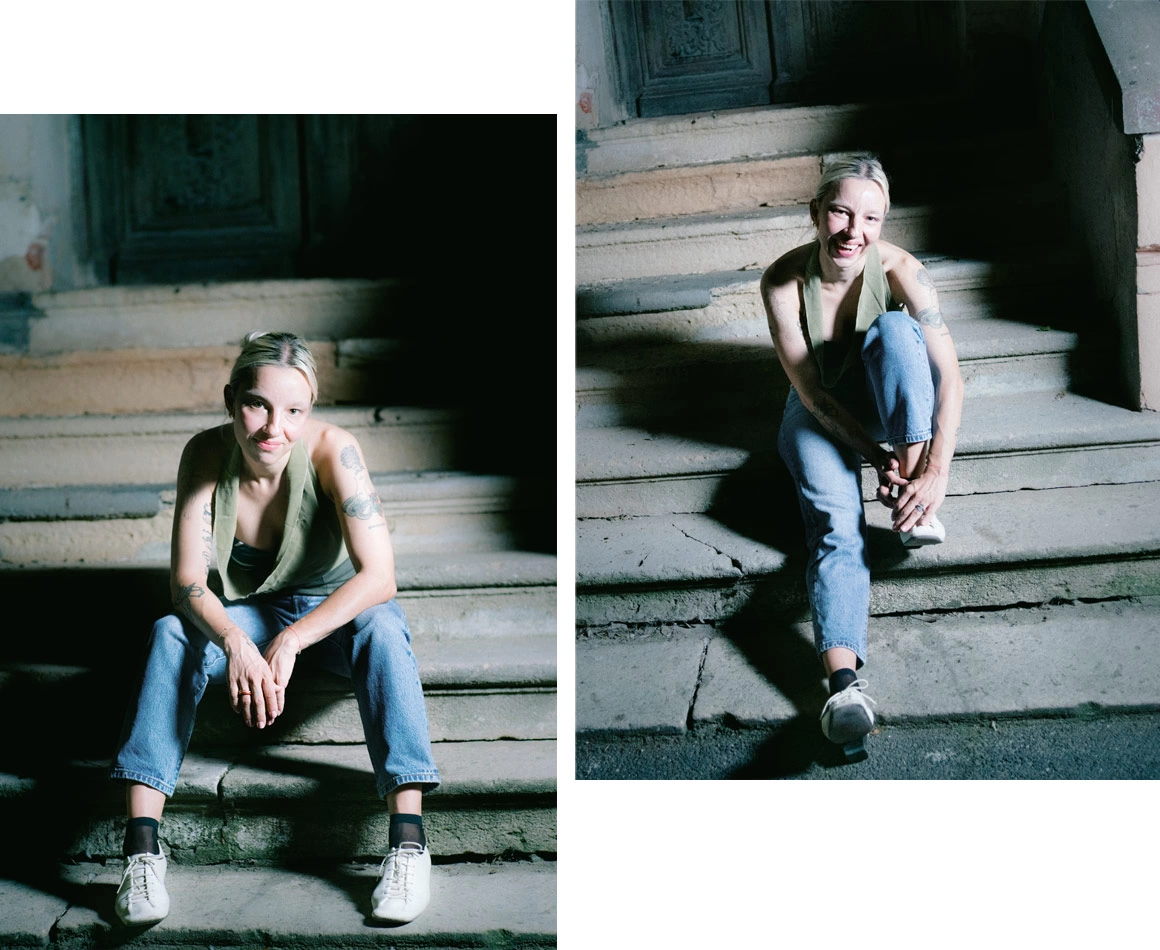

Dust swirls in the September heat, the facade of a high seismic risk building is demolished across the Eforie Cinematheque, and everything is somewhat post-apocalyptic and oddly fitting. Every time I meet Ilinca, whether by chance or by choice, she's as in motion as the character she played in front of the camera for four weeks. The film is on its festival tour, garners showers of praise, and Ilinca is on the emotional rollercoaster accompanying this sudden wave of attention. She’s a punk fairy in a pink velvet collar, gliding through Bucharest’s decrepit buildings, oscillating between contradictory inner states.

"Do you feel the chaos?" I ask her.

"I feel the chaos," she answers.

The first time we meet is at the bistro-bar Green Hours on Victoriei Avenue, a place she’s tied to by an intense artistic journey, / a place strongly connected to her artistic journey. The light falls at an angle on the wooden table, it’s hot outside and not yet dark, and people haven’t swarmed around the tables. The actress is split between film festivals, theater rehearsals, and saving stray cats she’s stubbornly seeking foster homes for. She’s equally voluble, playful and anxious, with a compelling voice and a contagious boyish laughter. She is warm-hearted and wants to thaw others. And she’s a good human being.

As I listen to her speak, I try to understand who Ilinca Manolache is, how fears and euphorias weave through her, what she’s trying to say when not saying a thing.

Once they wrapped up the shoot with Jude, she tells me, she felt the melancholy of the project ending – the sadness of parting ways with the atmosphere on set, with the unique experience of working on something that resonates so deeply with who she is and what she wants to do. In between one of our meetings and another, however, she realizes her bond with the film is still strong. Reviews dubbing the film a “formidable whorehouse”, “a delirium”, and her “an amphetamine-dazed Alice” flow in. And her anxiety scatters.

She recalls leaving Cătălin Cristuțiu’s editing studio the first time she saw the film. She wanted to "scream with joy and pride," she tells me laughingly. She was nervous about having to sit and watch herself filmed for hours. She feared she wouldn't like it, she has a sort of repulsion to seeing herself on screen. But she did it and said 'It's dynamite!'. From then on, only the pressure to do the film justice lingered, because she doesn’t want to mess it up when talking about a film that feels to her so important. A film about work, exploitation, fatigue, and death under the unscrupulous sign of capitalism. She’s glad she managed to imbue Angela's gestures with a certain vulgarity and sexuality. For the first time, she can say “with her whole being” that she’s "extremely proud" of what she’s done, that she no longer dissociates from the good things that happen and that she’s no longer demure for no reason. She’s sure she wants to do more cinema, but also more performance.

That’s because ever since she was a student, she felt something about the way we do theater here doesn’t suit her. She couldn’t figure it all out back then, but things have changed a bit in the meantime.

"They told me to take off my dreadlocks because I’m ugly and not a woman"

Ilinca Manolache was born close to the theater, grew up in the theater, started feeling uncomfortable in the theater, then began to question, confront, and challenge it.

Precisely because she comes from a family of actors, she suspects herself of laziness. She could have done anything else, she studied well. "But I never really had those moments where I asked myself, hey, what would I wanna be when I grow up?" She spent her childhood with the dressers, behind the curtains of the Small Theatre, during her parents' rehearsals, the actors Dinu Manolache and Rodica Negrea, and "that was it." "You keep going out of inertia and curiosity" – words of poet Vasile Leac come to mind, and immediately they feel unfair – you keep going for this is the world you grew up in and that fascinates you. Then, Ilinca tells me, "Actor parents have big personalities." The challenge was to create her own voice and identity, to separate herself from theirs. And that came in time.

If she’d been born into another family, perhaps she would’ve become a veterinarian. Ever since she was a little girl, she’s had a special bond with animals that you can still feel. Not squeamish about blood, she devotes significant amounts of her free time to saving kittens and has the intuition she would’ve made a good vet. Every time we meet, she amusedly shows me the cat food she keeps in her bag. Ilinca tirelessly posts Instagram stories about animals she seeks foster for, whether she’s in Locarno or preparing to promote the film in Los Angeles. She aches when she can't find any and runs against the indifference of people who can't see the suffering and the need for care that she sees so clearly.

The lives of the animals she saves consume her, but also confirm a much-needed humanity — for her job as an actress, but also for theatre as a whole.

Since she became aware of her surroundings, however, Ilinca dreamed indeed of becoming an actress – she wanted to be Andreea Bibiri at the Bulandra Theatre and act in shows directed by Ducu Darie, a director she was crazy about. Bulandra had been her beacon-theater growing up.

When her parents wanted to see if she had any penchant for acting, Dinu Manolache began taking her along to classes he taught at the National University for Theatre and Film “I. L. Caragiale” in Bucharest (UNATC). In 1998, when Ilinca was thirteen, he passed away, but she kept dreaming of being an actress. That’s how she ended up in the tenth grade at Cătălin Naum's Podul Theatre at the "Grigore Preoteasa" Student Culture House, a special place frequented by many of those drawn to the footlights. She pulled through, it seemed she had some "basic skills”, she tells me modestly, but had no backup plan. Confidence wasn't her forte, and UNATC didn't help with that later on either.

She faced challenges as a student and often wanted to quit. You couldn’t put her in a box, she wasn’t easy to label. "Neither beautiful nor ugly, neither a femme fatale nor an ingénue." The professors’ biggest issue were the dreadlocks Ilinca wore at the time. "They told me to take off my dreadlocks because I am ugly and not a woman." While she dreamed of playing roles of "beautiful women", like Titania in A Midsummer Night's Dream, they told her she could only play sexless spirits, say Puck in the same play. That hit a nerve at the time and still does. When she saw certain parts wouldn’t be given to her, she started unknotting her dreadlocks one by one with a needle. She couldn't have shaved her head either, "because that way I still wouldn't have been a woman." So she wore part of her hair, part dreadlocks, for about three years. Since then, a distorted self-image haunts her like a shadow.

This makes me think of the elven aura surrounding Ilinca at film festivals – of white trench coats in the limelight, of opaline eye-shadow and a mousy-playful attitude. I think of beauty, complexity and the absurd ways we label and confine each other. I think of Ilinca sliding her hands in her pockets and shifting her weight from one foot to the other when in front of a crowd – and that’s the only way to tell she’s uneasy. Of confidence. Of this almost androgynous ping-pong between what’s seen as feminine and masculine. I think of Ilinca watching herself from a distance and seeing herself as beautiful.

Many years after college, when she got her tattoos, a TV producer told her that "tattooed actresses are crackheads," while fellow actors and directors warned her not to get tattoos because she wouldn't be able to play anymore. "Exactly! I wanna get rid of everything I wouldn't be able to play if I had tattoos," she stubbornly replied.

She got rid of everything and she still played.

That didn't make her any less beautiful or any less of a woman.

In Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World, Angela Răducanu gives UNATC a glorious full-of-fury finger, speeding past the building on Matei Voievod Street. I recognize Ilinca's anger in there. Hers and many other actresses’ who’ve trodden the same hallways.

Because it's hard to speak up against a system that perpetuates its power.

"I thought you were an ingénue, but you’re a beast!"

In 2020, Ilinca began experimenting with the sort of social critique she practices today. With TikToks satirising the sleaziness and verbal violence used against women, or with humorous lip-syncs spoofing various characters in the media. It's been a while since she took on a politically engaged stance in the public eye. Even so, speaking out is not always easy.

She tells me she became “more outspoken” in her day-to-day life after graduating. At first, she feared "upsetting, bothering" someone with her attitude – because "you’re generally not allowed to speak out as an actress, it can cost you your job.” Once she managed to voice her first uncomfortable opinion, however, what others thought no longer mattered. What mattered was what she felt; if she felt discomfort, she said so. At that time, she was bothered by the Small Theatre director’s “big-boss” attitude. But she confronted him and suddenly the dynamic between them changed, she felt as if she had “gone up a step”.

She still finds herself in places where she feels she can’t speak her mind, where she feels this “ancestral shame”, as she calls it, and we both laugh. But this too is a means to shake off a discomfort suddenly arising in the body.

Ilinca Manolache is a theater professional, 38 years old, and plays one of the most memorable roles of Romanian cinema’s most recent decades. Despite this, she occasionally finds herself nonchalantly infantilized in public settings. This very summer, at the Anonimul International Independent Film Festival, Laurențiu Damian, a guest professor from UNATC, congratulated her on her role in Jude's film, just before perpetuating an age-old stereotype: "I thought you were an ingénue, but you're a beast!" He also made it clear he’d never cast Chekhov to an "adorable young actress" like her.

These things frustrate and anger me, for it’s the sort of belittlement that’s not even surprising, rather sad and old-fashioned – symptomatic of how the Romanian film industry, theater, UNATC, and others, still operate. They help me understand her and her frustration a bit better – as a woman, actress, and professional in the year 2023.

“This very conservative system needs to change”

At a table in Cișmigiu Park, we go on laughing about what doesn’t make us laugh. People throng the tables, beers pop in the background, and the Indian summer wind blows through the recorder. We talk and Ilinca is expansive and lavish in her answers.

In the years following graduation, she piled up frustrations and disillusionments, and the "great dramatic texts" began to fade in relevance. Those were the years she started craving their complete opposites – lively texts, written by flesh-and-blood playwrights whom she could work with, texts about the here and now. Productions that wouldn’t only aim to evoke some feeble emotion and send the spectator home, but also polish their critical spirit, push them towards asking questions and changing something around them. She believes there’s no such thing as art that’s not political. "It's impossible," she says. "Great artists who claim they make art for art's sake are really just keeping quiet and taking advantage of a system that favors them. But you're still political. When you're silent, you're complicit with power. It's that simple."

For a while, she found theater performances to suit her at the Monday Theater at Green Hours, a place she nostalgically recalls as "tying destinies like a knot." It was there and then she discovered a social-spirited independent theater, one she considered "way more radical and articulated 10-15 years ago" than it is today.

It all started when her then-boyfriend, actor and director Radu Iacoban, invited her to play a part in Nils’ Fucked Up Day – a punk-irreverent production by Peca Ștefan, “prohibited for minors and the ultra-prudish,” which they later took to New York. “From withered and wilted, as I got there on the first day, I slowly started to blossom”, she remembers somehow ethereally and wide-eyed. Even “opening her mouth” was scary at first. But the others laughed at her jokes, valued her acting, and she slowly began to feel part of a community. She built courage and confidence.

She’s glad she won the UNITER Award for Best Supporting Actress in 2016 with a theater performance by the same Peca Ștefan – The Vanished Year. 1989, staged at Teatrul Mic by Ana Mărgineanu. She’s happy that, although it was a show mounted in an institutional setting, it was produced and performed by the independents. She couldn’t have cared less about the prize itself. She’d dreamed of it her whole studies and when she finally got it, she’d already understood the power games going on behind the curtains and the prize didn’t matter nearly as much anymore. It had lost its glow and meaning. It was also a contemporary theater performance where all actors played leading roles, so the award verged on the absurd. She did not decline the honor but did not attend the award ceremony either. She wanted to have some articulated statement speech but didn’t manage to write it, so she didn't go. In that itself, however, Ilinca saw a statement: "By not attending, I stated my non-belonging to this very conservative system that needs to change."

“The repetition that theater implies breaks me”

Some independent theater spaces have vanished since then, and others still hold on. Reflecting on it, she tells me 'true independents' still exist, barely keeping afloat at the edge of subsistence, while there is another, only apparent independent theater segment that thrives by delivering a message that is not actually independent. Without challenging anything or anyone, they produce comfortable entertainment shows on the line and on big stages, such as those of the National Theater. With no cultural policies to offer a clear path, without a real interest in the impact theater can have in society, productions become arbitrary, Ilinca feels – “a vicious circle where the audience asks for something and the artists offer that something and that’s the key to success.”

Frustration led her to the point where she no longer wanted to do theater — she found her place neither among the independents nor at the Small Theater. She was soaking in a semi-mediocre comfort that had nothing to offer. Not because she no longer enjoyed acting — she believes she does her job at rehearsals, where she explores and discovers. But “the repetition theater implies breaks me'. She gets bored after the first few performances – it's all good at first, while the show is still fresh and there’s an exchange of ideas. But after three or four years, there’s a dullness inevitably setting in: “even if you no longer like the way you acted, you can't redo it, you can't suddenly change the show."

She discontinued many shows back then — some she played for six years — and frustration led her to experimenting online. Overlapping with the onset of the pandemic, this gave her the time and space to test out new ideas and tools. She tends to say she hasn’t done much in those two years, but the big pause was necessary to explore areas she might’ve overlooked otherwise. Her relationship to the digital, to the idea of community, to what it means to perform and self-perform, got then a complete makeover.

She finds theater, on the other hand, "carried on as if the world never stood still, as if this event that had affected the entire planet hadn’t happened, as if it never left a trace in our everyday lives." Theatre’s stringency, its inability to accommodate and integrate the new, to adapt to the surrounding reality, drives her out of her mind. "I don't know what should’ve happened, but something should’ve happened, so that it wouldn't be the same as before. I am not the same as before, no one is, why should theater remain exactly the same?". She feels the fear and reluctance of theater to blend with other media, to interweave itself with what is new and alive. In this sense, Radu Jude's film, with all its naughty formal quirks, with its radical disobedience, turned up just at the right time. There’s a need in Ilinca to mix different areas – to create hybrid, new, and untamed objects. Not only for art’s sake, but with an engaged social agenda.

The conversation turns playful – "maybe I'm saying something silly," she warns me and tells me of an idea she had the night before. She wonders how one can bring contestants from, say, Love Island, to the theater. Love Island is an entertainment show broadcast in Romania by Antena 1, where couples put their loyalty through tests on exotic islands. Following the American "Temptation Island" format, contestants are filmed and recorded 24/7, while handsome strangers referred to as "temptations" seduce them and try to dissolve their relationships.

She recently started watching the reality show as a sort of X-Ray outside of the culture bubble. She finds it fascinating to see various people, with their varying jobs and lives, to see present-day desirability standards in society. She wonders How could these people come to the theater and feel seen? Would they have anything to come to? How could theater have any impact on society when what happens on stage is so disconnected from the present day, from social reality? “We’re some uncles, some grannies, some nobodies and have-beens from, best case, the 2000s. Wannabe cool but not even. These people probably don't come [to the theater] because they have no reason to come. We are a mini-niche for ourselves, we have no impact in this society at all."

She’d like to find in traditional theater the need to touch and disquiet more layers of society. But this need is not there.

On the same note, Ilinca later tells me she's a devoted fan of RuPaul's Drag Race and has been wondering for a while when something of its kind will slay its way to Romania. In RuPaul's competition-by-elimination show – one that has won twenty-six Emmy Awards and is broadcast internationally – drag queens from all over America lip-synch, dress, dance and sashay for their lives and the epic title of "America's Next Drag Superstar”.

Recently invited on the jury of a Bucharest drag competition, however, Ilinca was awestruck – not only by the performers’ stage presence but also by their ability to form a community. “To me, they are heroines, seahorses, some sort of unicorns in this toxic and ultra-orthodox society”. She dreams of this scene mixing and blending in with theater, with the visual arts. “Things need to fuse a bit, ‘cause we can’t keep going like this!” – she’s almost shouting at me and we both laugh. Because she’s full of frustration, but also hope, and she finds it essential that we get out of our comfort zones, try out new things, and make mistakes. “It’s not cool to not mess up” – it’s precisely the moment you can spark a dialogue, learn, get feedback. “There’s nothing that can turn out wrong,” even if you make a mistake.

Now and then, Ilinca puts our conversation on hold and discreetly runs off to take snapshots of the passerby's outfits. Passionate about fashion, she has an Instagram page, Bucharesters in Bucharest, where she posts candid shots of the effortless styles found on the capital’s streets, in faceless and ego-free photos, a sort of local Parisians in Paris. Scrolling through random outfits, you can guess an almost anthropological taste – a different way of observing and documenting, a small archive of Bucharest’s street style through the filter of someone more accustomed to being seen than seeing. She’s developed an on-the-sly technique of taking pictures – she shoots quickly, without being noticed. She snaps the outfits catching her eye around us, we admire them, then go on talking about hybrid forms, the pandemic, and the online.

"And even if it turns out to be an absurdity, it's still more important than doing something you already know"

In 2020, Ilinca was rehearsing at the National Dance Center in Bucharest with artists Oana Maria Zaharia and Corina Sucarov for sex-ed activist Adriana Radu’s performance Portrait of the Artist as a Young Influencer. The performance investigated “the dynamics between intimacy, addiction and fame that girls and women experience on social media” as well as the relationship between “our identity in the real world as opposed to the one we display online in a controlled fashion.” Meeting the three women she admired, all of them flashing strong social media voices, made her aware of her own absence in the digital landscape. Although Adriana Radu’s performance denounced precisely the fakeness of the online world, in Ilinca the show sparked the wish to forge a voice just there. The one she already had – that of an actress employed by a state theater – seemed “corny”, “dusty”, “useless”, and “extremely unpresent in the present” / “extremely absent from the present”. The online was the tool she didn’t know she needed.

During the pandemic, along with actors Silvana Mihai and Daniel Popa, she created Everything Will Be Different, a performance-installation based on a Mark Schultz text. It had already been translated by Daniel years prior, it was supposed to be staged at Green Hours, but the overflowing schedule, the lack of money or prioritization of independent projects, made it so that it hasn’t been made.

The new surge of the online, however, opened up new opportunities and Ilinca brought up the idea of assembling the performance out of video calls. She was drawn to the text being "super explicit and sick in its writing," touching on "taboo subjects sparsely discussed in theater"— the first sexual impulses, the inability to truly connect with others, mental health, the death of loved ones. It would’ve all been too tame on a traditional stage, so they turned it into a YouTube theater-installation series under the aegis of the Small Theatre, all wrapped up in Instagram-story-aesthetics. Flashing a full arsenal of face-deforming, voice-changing, Christmas-lights-blazing filter effects, the video series plays precisely with the idea of fabricating oneself in the digital landscape.

Ilinca continued her online journey but wanted to connect straight to the people, without dramatic texts dictating her direction, calling her tune. "I wanted something truer, more concrete, more mine, more real, more radical, and more unmanufactured," she tells me passionately. This led her to create a kind of fresco of the Romanian everyday, but on TikTok, posting satirical lip-syncs with the voices of local media figures such as Dana Budeanu, Oana Zăvoranu, or Cristian Tudor Popescu. Although they got a lot of attention, she wasn't satisfied. They were too safe, too comfortable, more humorous than critical. They weren't radical enough.

“Yo, Bobiță!”

This is how she created, together with actress Ruxandra Maniu, totzik1, a social media project on the border between the online and the real. Totzik1 (to be read "Totzi ca 1", meaning All as 1, a name derived from a Romanian boyband of the 2000s) sports a silly name but juggles with serious matters. It is a feminist platform, an online video series, a space for venting and anger release, but also for collaboration and mutual empowerment. First things first, it’s a performative exercise where the actresses try to caricature and neutralize, as much as possible, something very worrying – the perpetuation of violence. They use filter effects, turn themselves into men, and become virtual versions of the harassers they denounce. It’s their way to steal a bit of their power and shake off the impact they have on women. They perform dialogues, expose verbal idiosyncrasies, oppressive language, and blow them up with humor. They make them funny. Ruxandra and Ilinca ultimately invite both a criticism and a dismantling of dominion devices, as well as play. A potentially offensive play, it’s true, but still a play – one that allows you to be someone you’re not and shake off that which you don’t actually need.

Moreover, they invite any woman to join them in this satirization of verbal violence they face every day. As a result, a small community of about seven women -- including actresses, performers, and directors such as Ioana Păun, Ilinca Hărnuț, Ana Popa, and Ioana Răileanu -- has formed around them. It meant the world to Ilinca that these women joined, as few of those around her actually approved of what she was doing, even if they understood her goals. The feedback was mixed. She was told "Okay, but why do we need this? This language and horrible energy are already everywhere. Why do you have to reproduce it?" “Well, because that’s how you condemn something” - Ilinca would answer - “you exaggerate and denounce this type of behavior, address, and approach to someone. Sure, there are other ways, but as an artist, as a performer, I have this ability and I wanna use it, criticizing, satirizing this type of dynamic.”

The experiment had already gone live for three or four months when Radu Jude told Ilinca he wanted to turn Bobiță into a character. Based on Ilinca’s performed smuttiness, he wrote Bobiță’s lines for Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World himself. Quickly, the avatar became the main tool for processing anger for both the actress and her character.

I admit to her I spoke like Bobiță for days on end after seeing the film for the first time. That I pawkily shoved my dick in all the losers acting like stupid cunts. That I felt great relief in allowing myself to be like that. I had great fun taking the Bobiță-tool to reflect back on all the horrible slurs I’ve heard over the years on the streets, in offices, in buses or in shops. Slurs that angered me, that I allowed myself to speak out against or not, but that somehow stayed within. I felt Bobiță was at once shocking, amusing, and liberating. She tells me this was the goal - the atrocities pouring out of this character’s mouth to be ridiculous. To be aggressive, but also spark laughter, for this is how you disarm. It was her way to shake off feelings of helplessness and anger using whatever she had at hand. To a certain extent, it worked. She couldn’t have known back then that Bobiță would make the rounds of international film festivals. Nor that, months later, the international press would see in him a resemblance to Andrew Tate.

Ilinca hadn’t heard of the goatee and bald-head misogynistic influencer when she chose the avatar’s filter effect. She jokes that there must’ve been the universe’s energies at play. On the day the former kickboxer, accused of rape and human trafficking, was released from custody, Jude's film premiered at Locarno, and Bobiță-the-misogynist-with-a-goatee-and-bald-head officially made his entrance onto the international film festival scene. It was as if Andrew Tate had stepped out of house arrest directly onto the oversized streets of the city. A kind of coincidence you can't really plan.

There are plenty of symmetries with the real world that Jude intentionally weaves into his film. Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World is a conversation with another era, between women who work and drive all day, before and after the 1989 revolution, before and after capitalism. But it’s also a conversation between Radu Jude with Radu Jude and, to a certain extent, a conversation between Ilinca Manolache and Ilinca Manolache.

If actors offer their acting and voice and face to the screen, that means there is a trace of documentary there, Ilinca tells me of a talk she had with Jude. This trace becomes ever more visible as the project Totzik1 makes it onto the screen, her frustration and fury are authentic, and her mother and partner in everyday life and her mother and partner on screen. None of them likes seeing her as a bald foul-mouthed moron insulting women online. However, she continues to do it – both as Ilinca and as Angela – and this is empowering for both.

We start to wonder where fiction ends and reality begins. How much of fiction is documentary, how much of the archive is fiction, how much of Ilinca's nerve and attitude are in Angela? But there are no clear boundaries. She herself becomes part of the game between truth and falsehood she’s been exploring for the past years. Amidst digital performances, social critiques, and uncomfortable experiments, she becomes a sort of Ouroboros snake, biting its own tail.

"We’re racists, we’re homophobes, we’re misogynists, ‘cause that's how we were raised, but we can do better"

The chaos Angela lives in is the chaos Ilinca lives in as well. Some mornings she wakes up and “wants to scream”. Living on the first floor right above a grocery store, bales of goods are loaded and unloaded daily in the early hours and the noise is infernal.

Both in the film and in real life, she has an articulated, incisive, oftentimes destabilizing stance, sprung at once from frustration and courage. Her practice makes me think of the ability to lay oneself open in an environment rarely friendly to those who step outside the box and shake it. Of a certain self-confidence, but also of the support of a community. Whether we’re talking about remixed forms of theater or performance, TikTok, Instagram, or YouTube video series, or whether we can't name them because these kinds of intermedialities haven’t yet been named, Ilinca uses the tools at hand to move something in the society around her.

She would like society to change. She would find it ideal to work "in an environment where false power differences no longer exist, where we respect one another, and where there are no more structures of power and dominion that lead to no good".

But transformation takes time. I ask her how we can better take care of each other in the meantime.

“I think we could look after one another if we learned how to listen to each other”, she answers. She tries to apply this to herself – when criticized, to not get upset, to accept we’re all human and we all make mistakes. “Unfortunately, we live in a society where racism exists, homophobia exists, and we all have them in us.” Ilinca is determined to change herself first and learn how to mend her behavior –“I don’t have it because I’m bad. I have it because I grew up in a society that has the chance to be better if everyone learns and gets the feedback that leads to improvement.”

***

I see Ilinca in the movie theater watching herself on the big screen and no longer feeling repulsion. She shrinks in her seat, puts her hands on her face, and tries not to laugh too loudly. Bobiță scenes touch her the most. There’s shame and there's explosive enthusiasm. And the pride of having dared and keeping on daring.