Media literacy classes for teachers and parents in Romania, participatory theatre in Spain, hotlines and cyber police in Ukraine – these are just some of the solutions organisations and institutions are using against the ever evolving forms of violence children and teenagers face more and more often in their digital lives.

From cyberbullying and cyberharassment, exposure to harmful content and hate speech, to online child sexual abuse and exploitation, statistics show they are all on the rise, and digital safety for the youngest citizens has become a global concern. The accelerated development of AI only adds complexity, generating new forms of cyberviolence, like deepfake nudes and deepfake porn, which only deepen the already serious emotional and psychological risks brought by long screentime.

For many parents and educators, the digital world feels overwhelming. A recent Flash Eurobarometer shows that 82% of the people in the survey agree that tools like parental control are no longer enough to keep children safe online. Schools are only just beginning to face the complex forms of violence kids experience in their everyday lives, while authorities, often unaware or unequipped, struggle to respond. Legislation lags behind, and tech companies remain mostly silent about the threats perpetuated on their platforms and networks.

In this intricate context, what tools, laws, or protection measures do we have against the amplifying forms of online violence that affect millions of young people? What’s actually working and how can we, as societies, build safer and more supportive online spaces for children and teens?

These are just some of the questions explored in this cross-border investigation by Scena9 (Romania), Maldita.es (Spain) and Rubryka (Ukraine), with support from Journalismfund Europe. This is the first article of a series focused on working solutions which various organisations and institutions from these three countries have come up with against an ever growing series of digital, borderless crimes. You can read the rest of the articles at Scena9, Maldita.es and Rubryka websites.

How is digital violence affecting minors? Facts and numbers

A 12 year old Romanian boy was tricked by older school colleagues to show his genitalia in front of the phone camera. They photographed him and shared the images on several Whatsapp groups, humiliating and blackmailing the boy. In Spain, 16 high-school girls reported their images had been modified with AI to show them naked. The material - created by a minor - was distributed on social media and a website. In Ukraine, a stranger offered a girl a job. The essence of the job was that the girl had to take and post her intimate photos on the Telegram channel.

These cases may all seem different, but they are all forms of online violence children and teenagers have been experiencing more and more in the last years. Children today grow up with technology, often mastering devices before they can speak. The majority of kids get their own smartphones by the age of 10, but many of them are already exposed to screens since they are toddlers. By the time they are 12, 75% to 97% of European kids usually own their own smartphone. According to a study in 19 European countries, 80% of children aged 9–16 use their phone daily or almost daily to go online and the time they spend online keeps expanding. On average, a 12 year old kid in the EU spends about 3-4 hours online everyday, but the actual numbers may be considerably higher. 27% of the Romanian children and teenagers in a recent survey by Save the Children admitted their daily screen time is around 6 hours.

Behind those screens, there are risks and dangers with a particular characteristic: digital violence never ends; it lasts 24/7. A 2022 study led by the International University of La Rioja found that 6% of adolescents in Spain suffer constant cyberharassment – girls are, to a significant extent, more likely to be continuously cyberbullied than boys.

According to the World Health Organization, almost 17% of European children aged 11 to 15 have been bullied by their peers online. Since 2018, this number has been steadily growing. Spain has reported a 57.5% prevalence in cyberbullying, the highest among the other countries analyzed in a study conducted by Frontiers in Public Health. Half of Romanian children also admit they were humiliated or harassed online, and in Ukraine, online violence against children has only been aggravated by the full scale Russian invasion.

39.8% of Ukrainian children aged 8-10 saw pornographic content on the internet for the first time, and in most cases, this happened unexpectedly, through ads on social networks or games. A report by UNICEF found that a significant number of children aged 12–16 have been exposed to violent, sexual or other inappropriate content online, which can contribute to psychological distress. Spain and Romania are among the countries where children have the highest risk of accessing harmful content online.

Among the forms of online violence young people experience in their daily digital lives, those related to sexual abuse are extremely widespread and dangerous. The latest report from Internet Watch shows an increase of child sexual abuse imagery hosted in EU and that “every 108 seconds a report [monitored by the organisation] showed a child being sexually abused” online. In most cases, the images used are „self-generated”, which means that a child has produced images or videos of themselves.

At the same time, schools from all over the world, including Spain, Romania and Ukraine, are facing an “epidemic” of deepfake nudes. Students, especially boys, are using generative AI to create deepfake nude photos of their colleagues or synthetic pornographic videos, which they share without any consent in private conversations, on social media or on adult content websites.

Together with the increasing time young people spend on social media, exposure to such a diversity of digital violence takes a significant toll on their mental health. But despite the staggering statistics, children and teenagers are not always taught how to stay safe online. Families, schools and institutions struggle to navigate the complexities which allow the proliferation of cyberbullying, grooming, sextorsion, revenge porn, deepfake nudes and others.

We searched for effective solutions in Spain, Romania and Ukraine. They appeal to culture, technology and law, as digital violence is not one single problem, but rather an intricate web of problems and challenges, which affect our lives in an unprecedented way.

Theatre and other cultural initiatives against cyberbullying and digital violence

In Spain, various cultural and educational initiatives are being promoted to raise awareness and prevent cyberbullying and other forms of digital violence among minors. One of the most notable is theatre, which creates immersive experiences capable of arousing empathy and encouraging reflection.

This is the case with the play Aulas, by playwright Carlos Molinero, which has been performed in Spain some 39 times in three years for around 4,800 spectators. It allows the audience to interact via WhatsApp and decide the ending. This way, it enables spectators to put themselves in roles they have never experienced before. Other productions, such as Girls Like That - an adaptation of a play by British playwright Evan Placey, by the Catalan company Càlam, about the dissemination of intimate images without the consent of the protagonist - or La Liga Contra el Bullying (The League Against Bullying) - with magic and child participation, by the company Espectáculos Educativos - address real issues in a language that is accessible to young people. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the latter company has performed between 150 and 300 shows of all its plays per year.

The experts consulted by Maldita.es agree that these initiatives must be accompanied by educational resources to reinforce the concepts and lessons learned from the performances. Girls Like That provides teaching staff with a dossier that they can use to continue developing activities in the classroom, and the authors of Aulas have developed an interactive teaching booklet with materials and activities for the same purpose. In addition, in both cases, a discussion takes place after the performance.

Participatory theatre encourages communication, creativity and conflict management, generating positive changes in attitudes and behaviour. Furthermore, paratheatrical techniques developed by associations such as AEPAE, the Spanish Association for the Prevention of Bullying, have proven useful in empowering victims: through physical assertiveness tools, camps and psychodrama, children improve their self-esteem, expressive abilities and confidence in the face of bullying. "You can see an evolution in their physical and verbal attitudes. They are no longer children who simply raise their heads and look at you; now they are able to express their thoughts, feelings and emotions," explains Goyo Pastor, co-founder of AEPAE and professor of dramatic arts at the Royal School of Dramatic Arts of the Community of Madrid (RESAD for its acronym in Spanish).

According to a 2023 study on the effects of psychodrama on adolescent health, this technique demonstrated positive effects on various aspects of mental and social health, including reduced anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, frustration, and oppositional defiant disorder, as well as improvements in emotional regulation, aggression, conflict resolution skills, forgiveness, self-esteem, and communication.

Apart from theatre, other culture-based resources are also proposed for prevention and education. Organisations such as PDA Bullying work with series such as Adolescence and Skam, and recommend reading novels such as La Guarida and El infinito en tus manos, which encourage reflection on power dynamics, online humiliation and the responsible use of technology. These materials include teaching guides and activities for teachers and families, which facilitates their integration into the classroom. Research supports their effectiveness, especially when accompanied by discussions and exercises after viewing or reading.

Training programmes, camps and workshops aimed at children, families and teachers are also being developed. It’s the case of initiatives such as E-tic (promoted by the Diario de Navarra Foundation) and its programme on digital education and well-being, which has been running for three years in schools in Navarra (Spain) and has benefited more than 3,600 pupils. Nerea Tollar, educational coordinator at E-tic, explains that the aim of the project is ‘to go into schools to educate pupils, but also their families’, promoting conscious and safe use of the internet. Other initiatives include Campus Fad and Te pongo un reto, which offer practical training on digital risks (cyberbullying, grooming, sextortion and hate speech).

However, these proposals face limitations that reduce their scope: the absence of institutional support, the lack of integration into the curriculum and the high costs of many activities. Experts agree that, in order to enhance their impact, it would be necessary to include them in the school curriculum, establish evaluation mechanisms and secure public funding to ensure their continuity and accessibility.

Artificial intelligence and technology: a problem and a solution to cyberharrassment

Online violence against minors has also manifested itself in new ways in recent years. “I knew these tools existed, but I never imagined they would be so accessible, or that they could be used with such impunity among minors. And even less so that one day something like this would directly affect my daughter.” This is how Miriam Al Abid describes her experience to Maldita.es: her daughter is one of the victims in the case of the dissemination of AI-generated nude images in Almendralejo (Extremadura, Spain), which affected 22 minors in 2023. Those identified as responsible were also minors.

Maldita.es has compiled at least 14 reported cases of AI-generated sexual content involving minors in Spain between 2023 and 2025. According to a 2025 report by Save The Children, 20% of young Spanish say that someone shared AI-generated images of them naked while they were minors and without their consent (21% of girls and 18% of boys).

It is a global problem: a 2023 study by the Internet Watch Foundation analysed a dark web forum and in just one month found 11,108 AI-generated images suspected of infringing on child sexual abuse offences. And it is becoming increasingly easy and accessible to do so. There are mobile apps available in app stores, websites specialising in deepfakes, bots on Telegram that strip images, and even AI image generation tools, such as Grok, that allow users to create content that sexualises people.

Such AI-generated sexual content can constitute a child pornography offence and impact the mental health of minors, who also become victims of disinformation: these images do not actually reflect their bodies or their actions. “The victim is disinformed, manipulated and their reputation destroyed in the same way as revenge porn or sextortion,” explains Rocío Pina, professor of Psychology and Education Sciences and the Criminology degree at the Open University of Catalonia.

AI is therefore at the heart of the problem (AI is also being used to perpetrate cyberharrassment through humiliating memes and stickers or fake profiles that impersonate victims), and in many cases it is minors themselves who use it against other children and adolescents. “[Minors] have too much access to AI tools without being prepared for it, and even their parents don't know how it works,” says Laura Cuesta, professor of cybercommunication and new media at Camilo José Cela University in Madrid.

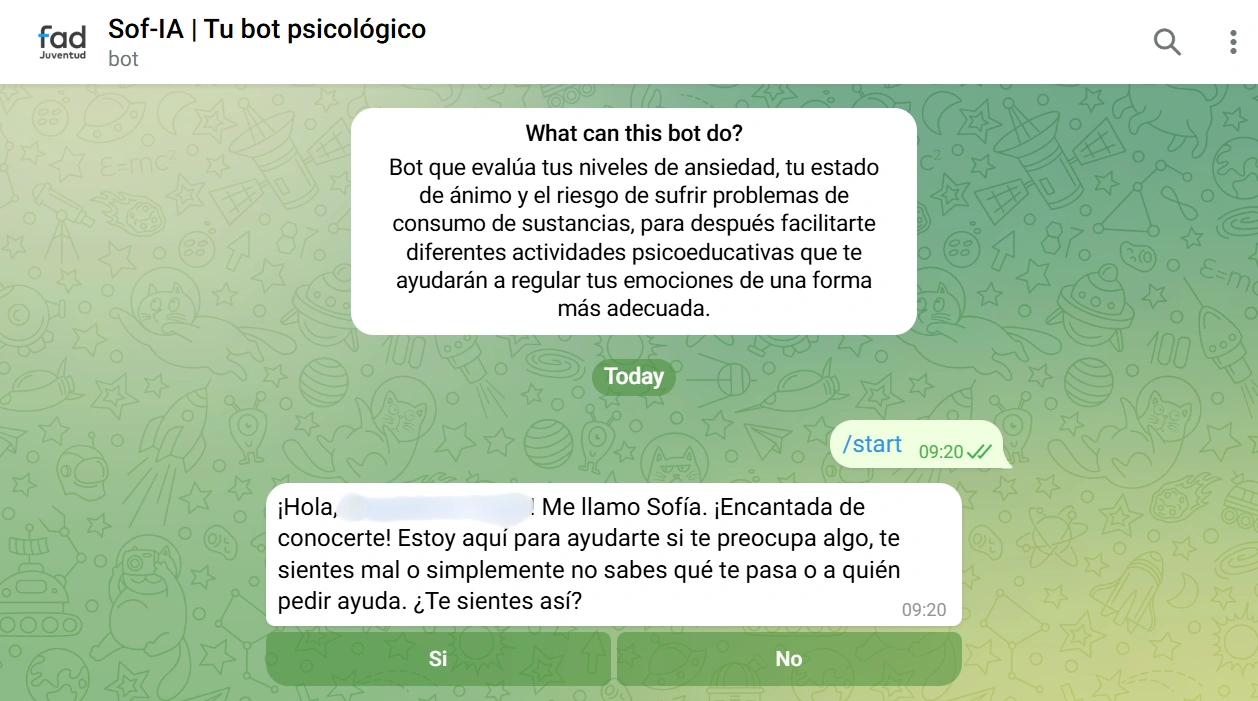

But, on the other side of the coin, it can also be part of the solution. One of the AI-based initiatives being developed in Spain is Sof-IA, the AI chatbot from the Fad Juventud foundation. This chatbot “handles queries related to substance use, as well as emotional distress, including situations of digital violence,” according to the foundation's explanation to Maldita.es, and is designed for young people who “do not want or dare to write to a service staffed by a person or prefer the anonymity of chat.” Since its launch in 2024, Sof-IA has handled more than 800 queries, according to the foundation, although the initiative still has limitations such as a lack of interactivity, content that is “somewhat brief or simple,” and the fact that the chatbot is only implemented on Telegram.

How Do We Keep Children Safe from Online Violence and the Challenges of AI

Another proposal is DEL.IA, an assistant against hate crimes developed by students of the Master's Degree in Language and Artificial Intelligence at the Autonomous University of Madrid. Its aim is to advise users on how to report hate crimes in physical and digital environments, where we may encounter haters, trolls and hate speech. The assistant uses voice recognition to “guide the victim empathetically,” according to the master's website. The initiative was launched in 2025, so there are no figures available yet on the impact of the project or its projection, but in general, it should be remembered that any AI project may have the limitations associated with this technology (errors, hallucinations and biases).

In addition to possible AI solutions, there are initiatives that seek to promote critical thinking and digital education on artificial intelligence to curb digital violence against minors. This is the case with both E-tic (teaching families and minors to differentiate between AI-generated content and real content) and Fad Juventud (training materials and courses for minors, families and teachers to educate teachers and parents about AI).

Bringing Digital Education & Media Literacy to Romania

“I had grown men commenting on my posts, saying they hoped I would be raped, just because I dared to disagree with some posts that were inciting hatred,” writes a 16-year-old girl in a questionnaire created by Scena9 for this article. Another teenager recounts how a former boyfriend secretly took pictures of her while she was changing clothes, then published them without her knowledge on a Telegram channel with a thousand users and sent them to all her friends and classmates. A few dozen other teenagers shared their experiences with digital violence, which, they say, they had no one to talk to about. Most of those who completed the questionnaire say that, in such situations, they do not turn to their parents for fear of being blamed and punished. They want more understanding and information from adults on topics related to intimacy and consent.

At the same time, most parents, although they agree that their children's safety on the internet is a major concern, don't know where to start. “I’m afraid of setting too strict limits for my child and seeming too tough,” says a mother participating in a workshop organized by the Zi de Bine Association, in a project aimed at combating various addictions among teenagers, including phone and social media addiction. Starting from similar situations, the association developed a project to offer parents concrete tools: a series of workshops led by psychiatrists and psychologists, as well as a “digital detox” camp for teenagers, where they would spend time without a mobile phone. Gabriela Gocan, the coordinator for the project focused on behavioral addictions, noticed a huge desire from parents to find solutions, given that some of them see their child trembling if their phone is taken away or withdrawing from the relationship with the parent as a rebellious act. That's why a more balanced relationship between children and technology must start in the family, and parents greatly need to better understand the digital worlds their children live in and how they can support them to be safe. In the future, Zi de Bine wants to introduce a media literacy component into this program so that young people can learn to use their time online more efficiently, understand the mechanisms of the platforms they use, and know how to ask for help if they need it.

Digital education is almost completely absent from Romanian schools and, when it is present, it often fails to connect with young people. “Some absolutely unprepared and disconnected people come to teach us how to protect ourselves [from abuse],” a teenager replied in our questionnaire. She believes that media and sex education should be taught starting in primary school. “I would like to see serious people teaching these things, people who are constantly talking with young people to keep up with the present, gentle and empathetic people you can talk to.”

Although subjects that help children and teenagers stay safe in the digital environment are missing from school curricula, several organizations are trying to fill these essential gaps. Cristina Lupu, from the Center for Independent Journalism (CJI), has been organizing media literacy courses with teachers and students all over the country since 2017. The program, focused on how algorithms and artificial intelligence work, how to detect fake news or a deepfake, is supported by the Ministry of Education. Among these topics, the mentors also include information about violence in the digital environment. So far, it has reached 10.000 teachers, 290.000 students in 462 Romanian schools. A course lasts 60 hours, and the graduating teachers are then integrated into a two-year mentorship program with monthly meetings where they debate a specific topic. The teachers then integrate the information and methods learned from digital communication specialists into their classes. The idea of the program is to make the participants feel part of a community of change that produces long-term effects. “We don’t believe that training is enough though. You can’t expect that you do a course and things are solved,” explains Cristina Lupu.

At the same time, the schools they have reached are in large cities with a higher level of education, where people are more open to questioning their own biases. But even here, victim-blaming is part of the mentality of many teachers. “It’s still difficult because you have this idea: Was it her fault too? Didn’t she know not to do that? Didn’t she know not to walk on the street at night?” explains Cristina. “A major obstacle is to understand that at that age it’s normal [to send photos], no matter how much I tell them not to do it.”

The “Start in Education” and „I want in 9th grade” programs led by international foundation World Vision Romania, are among the very few initiatives that bring elements of digital education to schools in rural areas. They organize information and awareness sessions about all forms of violence against children. Teachers, parents, and students receive brochures with concrete steps they should take in case of abuse, for example, to gather evidence and go to the police. However, the barrier that Mihaela Voicu, a child protection specialist at World Vision, sees with parents, for instance, is the disciplinary approach. “Many of them still consider that a beating is a gift from God and it’s a parent’s right to educate their child with beatings,” she explains. “You can imagine how that mother or father would react, they would blame the victim for exposing herself, for getting into inappropriate discussions.” For the year 2024, the foundation reached through their programs a total of 179.779 beneficiaries: 59.882 adults and 119.897 children.

Both Cristina Lupu from the Center for Independent Journalism and Mihaela Voicu from the World Vision Romania foundation believe that the school counselor can play an important role in managing a case of online abuse in schools. On the one hand, the task of managing such cases would no longer fall on the teacher during class, but on a person trained to help a child who is affected, in this case, by mental health issues. “I don’t ask chatgpt, ‘What should I do if…?’ I go and talk one-on-one and look into the person’s eyes and feel the empathy and the joy of communicating, of having a human discussion with someone, with a professional who knows how to help me get through it,” believes Mihaela Voicu. The reality on the ground shows that, in the 2023-2024 school year, a single counselor was responsible for 800 students, and their total number in Romanian schools was just over 3,000.

Emergency Hotlines for Reporting Child Sexual Abuse Online

In this context, beyond media education, programs like “Ora de Net” from Salvați Copiii (Save the Children) become essential tools. The organization is involved in monitoring the abuse children face in digital spaces, counseling victims who ask for their help, and trying to raise awareness among children and parents. “Ora de Net,” which started 17 years ago, follows three directions: studies that analyze the online behavior of children and parents, educational sessions in schools, and esc_Abuz, an online platform where anyone can report experiences of abuse or dangerous situations on the internet. An important pillar of the program is the involvement of young people in promoting online safety. Teenagers over 15 can become volunteers and “Save the Children” ambassadors, participating in training about digital risks, brainstorming sessions, and focus groups. They then go to schools to talk to their peers about how to protect themselves in the online environment.

“esc_Abuz” is an online reporting line where notifications or anonymous reports regarding child abuse material on the internet can be submitted through a form available on the dedicated website. The content reported here is analyzed by an operator to determine whether it represents child sexual abuse and to verify the location of the server where it is hosted. If it is found that the material contains images depicting child sexual abuse and the server is located in Romania, the report is forwarded to the General Inspectorate of the Romanian Police. If the file is hosted on a server abroad, it is redirected to the appropriate reporting line within the INHOPE network, which takes over the notification.

A practical solution for managing cases of abuse of any type among students comes from the Children’s Consultative Council, a group of young people affiliated with the World Vision Romania foundation. In 2024, they proposed to the Ministry of Education the establishment of an online platform through which violence in schools can be reported anonymously, nationwide. In this way, they believe, the shame and fear of being blamed as a victim will no longer be obstacles to reporting. Following a report, the school should have a clear procedure to apply for its resolution.

If there were political will, Romania could learn how to build an effective solution to reduce digital materials with sexual content that affect children and to better monitor the abuse around them. The British organization Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) has the largest reporting hotline in Europe and is one of the few, globally, that has legal powers to proactively search for online child sexual abuse materials. The organization, created almost three decades ago, noticed that the problem of online child abuse has no borders. That's why it tries to collaborate with institutions, authorities, people in tech, organizations, and hotlines from other countries to see the effects they desire. When Internet Watch began its activity, 18% of the known worldwide content depicting child sexual abuse came from the UK. Today, less than 1% of these images originate from there.

IWF analysts spend hours every day in front of screens to identify and remove child sexual abuse materials. Their hotline, led by Tamsin McNally, operates through three teams: analysts, evaluators, and quality assurance. The analysts verify public reports, collect evidence, and collaborate with authorities to remove the materials. The evaluators analyze each file, determine its abusive nature, and generate a digital hash to prevent its spread. Because the work is emotionally extremely difficult, the 40 members of the hotline have access to psychological counseling and must participate in yearly sessions with psychologists. “I say this often: I wish my job didn’t exist. It would be wonderful if, one day, we could say the problem is solved. Until then, however, we will continue to gather data and take steps forward,” says Tamsin McNally, the coordinator of the Internet Watch Foundation hotline, which will serve as a model for a future European hotline.

Hotlines, cyber police awareness campaigns: Ukraine’s multi-level response

“...the guy demands that the girl continue to send him her nude photos, otherwise, he will send all her intimate photos that he already has to her relatives, friends and acquaintances”. “...the stranger offered the girl a job. The job required the girl to take and post her intimate photos on the Telegram channel.” These are the types of requests that consultants of LaStrada-Ukraine, an NGO focused on human rights, receive from children and teenagers via an online reporting system and hotline.

Another similar initative comes from the NGO Magnolia, which became part of the international INHOPE network of hotlines, together with the Ministry of Digital and Cyberpolice in Ukraine. They launched StopCrime, a portal for anonymous reports of online sexual abuse against children. In the first half of 2025 alone, this portal processed more than one and a half thousand calls, hundreds of which were transferred to law enforcement agencies in Ukraine and abroad. In addition, the 116 111 hotline, devoted to reports of missing children and cases of violence, organizes information campaigns for parents, teachers and children themselves. This is part of the efforts the Ukrainian state makes, in cooperation with the public sector and international partners, in order to build a response to online violence against children, that combines rapid response to crimes with prevention and education.

Analysts of Magnolia, members of the Safe Internet Center, check the calls daily. In the first half of 2025, analysts processed 1,538 reports, of which 812 confirmed to be cases of online sexual violence against a child. The least they can do is to remove these files from the network, while in some cases they initiate an investigation of the crimes, in order to punish the perpetrators. 62% of the 812 confirmed facts of sexual violence have been transferred to the cyber police of Ukraine, while the remaining 38% to law enforcement agencies of other countries, and in 4 criminal proceedings, where StopCrime analysts act as witnesses.

“The biggest problem is that only a few people contact the police with complaints about sexting or grooming,” says Olga Sheremet, coordinator of the Safe Internet Center, a cluster of organizations that seek to protect children from the very real threats of the virtual world, of which NGO LaStrada-Ukraine and Magnolia are part of. “Ukrainian children are regularly offered to share intimate photos on the Internet, they are sent messages with sexual overtones, erotic photos or videos”. According to Sheremet, most of the delicate situations where children risk or become victims of sexual violence online remain undiscussed with adults. “Children are afraid of shame, punishment, and misunderstanding. And this is not surprising,” says Olga Sheremet. „After all, media literacy and digital hygiene are what Ukrainian children, their parents, and often Ukrainian teachers lack. Sometimes a child does not have that reliable adult in his environment to whom he can turn for help. And these are challenges to which the education system needs to be adapted, preventive measures introduced. Actually, that is why our projects were created: StopCrime — so that a person can anonymously complain about unacceptable material with the participation of a child on the Internet, and the Safe Internet Center portal — where a responsible adult will definitely find tips for himself on how to talk to a child about delicate topics, where to turn for help…”

The cooperation of Magnolia, also part of Safe Internet Center, with the cyber police within the framework of the StopCrime project, is quite productive, according to Olga Sheremet, coordinator of the Safe Internet Center. “The harmful links that we receive on the portal are promptly blocked after verification. At the beginning of the year, providers of child pornography, whose owners or tenants are citizens of other states, remained a big problem. But after numerous appeals, the Cyber Police Department and the State Service for Special Communications and Information Protection of Ukraine found a solution to block the domain names of providers of such «services». We consider this a major breakthrough in the fight against violence on the Internet,” says Olga Sheremet.

Thus, in March of this year, cyber police officers in the Khmelnytskyi region arrested a man who distributed child porn for money. The police say identifying the perpetrator became possible thanks to the functioning of the StopCrime project. Citizens sent web links to illegal content to the portal, and Magnolia operators analyzed it and sent it to the cyber police. The criminal has already been detained - he now faces 15 years in prison.

In order to prevent cases of violence against children in Internet, the Safe Internet Center also conducts information and educational activities: these include showing films in schools, expert discussions with educators, law enforcement officers, parents, journalists, and human rights activists, distributing memorabilia, and conducting webinars for educators and inspectors of the Educational Security Service of the National Police of Ukraine.

These are all part of Ukraine’s strategy for gradually building a multi-level system for protecting children in the digital environment. The cyber police conduct special operations and block resources that distribute child sexual abuse materials. In 2025, they managed to stop the server hosting 70% of child pornography in the Ukrainian digital space.

At the same time, the Ministry of Education and Science launched the AICOM platform, which allows schoolchildren, parents and teachers to anonymously report cases of bullying and cyberbullying. The Ministry of Digital Transformation offered interactive online safety tool on the Diya.Osvita platform. The tool allows you to report bullying in an educational institution anonymously or openly, and this data will be transmitted to the director of your educational institution. The director must respond to the bullying report, however, if this does not happen, the bullying response algorithm provided for by current legislation will be activated within 24 hours.

The private sector has also contributed its tools: Google Ukraine opened the "Children's Safety on the Internet" platform, with materials for teachers and parental control tools.

Ultimately, the success of these initiatives depends not only on laws and technologies, but also on building a culture of trust and awareness. Children must know that they are not alone and that there are adults and institutions ready to listen and help. Parents and teachers also need to be equipped with the knowledge and tools to talk openly with children about online risks, without fear or judgment. Ukraine’s experience shows that the combination of rapid response mechanisms, preventive education, and active involvement of civil society can significantly reduce threats and protect the most vulnerable. The digital environment will never be completely free of risks, but through cooperation between the state, private sector, NGOs and international partners, it can become a safer place for every child.

The debate on banning cell phones in classrooms and their effectiveness against digital violence

Banning cell phones in classrooms is another possible solution to reduce the problem of digital violence against minors and AI-generated content. Some countries have already taken this step: Portugal will ban them from the 2025/26 school year in the early stages of education, after an evaluation of the implementation of this measure in some schools revealed that bullying had decreased, and France, who banned their use in 2018, is considering tightening the measure.

In Spain, the State School Council recommended in 2024 that cell phones should be completely banned in primary stages, and its use should be only allowed for educational or medical purposes in secondary schools. However, there is no single rule at the national level, and the regulation of personal electronic devices in classrooms varies from region to region: some autonomous communities in Spain ban them completely, others have nuanced rules, and others leave the decision up to the schools themselves.

The Department of Education and Vocational Training of the Región de Murcia - an autonomous community in Spain that banned the use of mobile devices in primary, secondary, and vocational training classrooms in January 2024 - told Maldita.es that the measure has led to a "notable improvement in coexistence in educational centers, with a reduction in very serious offenses and a decrease in cases of cyberharrassment." Specifically, there was a 27.42% decrease in reported cases of cyberharrassment between 2023 and 2024. There are also studies, such as an analysis by researchers Pilar Beneito and Óscar Vicente-Chirivella from the University of Valencia (Comunidad Valenciana, Spain) and research from the University of Augsburg (Germany), which defend the effectiveness of these measures in reducing bullying in schools.

In Romania, the use of mobile phones during classes is banned. At least on paper. Although the law was changed last year, and the Ministry for Education announced phones would be completely banned during the entire school program, including during breaks schools have the freedom to decide their own policies regarding this issue. This leaves the door open for exceptions. Half a year after the phone ban was announced by the Ministry of Education, Daniel David, the head of the institution, told the press he does not support such a measure. He only recommended schools to adopt strict measures.

In Ukraine, there is no complete ban on mobile phones in schools at the legislative level, but the institutions themselves can establish their own rules for their use. Each school has the right to independently develop and adopt rules regarding gadgets, which must be followed by all participants in the educational process. The education ombudsman notes that schools cannot prohibit students from having phones, but they can restrict their use during lessons. The situation is complicated by war. During war, giving up gadgets during lessons is impossible. Many children study remotely, and being present at lessons and giving up the Internet at the same time is simply impossible.

On the other hand, experts consulted by Maldita.es think that a total ban is not the answer (banning can have the opposite effect and minors still have access to devices after school). They all agree that digital education for minors is key. “Education has to do with raising awareness about the good and bad that can come with the use of new technologies. We believe that prohibition as such does not solve the problem,” explains Ferran Calvo, president of the Baobab Association.

From age verification systems, to criminalizing AI generated sexual content: legislative framework to curb digital violence

Regulation as a solution does not apply exclusively to the prohibition or not prohibition of cell phones; it is also necessary to prevent and respond to situations of digital violence. In the European Union, Spain, Romania, and Ukraine, there are legislative frameworks in place and bills that seek to update regulations to address new issues, such as classifying sexual content created with AI as a crime.

At the European level, the main regulation seeking to protect minors online is the Digital Services Act (DSA), a set of rules governing the digital space that includes measures on transparency, content moderation, misinformation, and recommendation algorithms. On July 14, 2025, the European Commission published its Guidelines on the Protection of Minors under the DSA, "to protect children from online risks such as grooming, harmful content, problematic and addictive behavior, as well as cyberbullying and harmful commercial practices." According to Asha Allen, Secretary General of the Center for Democracy and Technology Europe (CDT), declarations to Maldita.es , “the Digital Services Act provides the most comprehensive framework for the online protection of minors as it sets the parameters for platform obligations in tackling illegal content as well as mandatory due diligence and transparency obligations to address ‘systemic risks’, of which the protection of minors is explicitly included”.

Laws like the DSA require very large platforms (VLOP) to introduce age verification systems to protect minors from content that can be damaging. However, the development of stricter systems remains a topic of debate due to the privacy issues they could entail. Ella Jakubowska, Head of Public Policy at European Digital Rights (EDRi), explains to Maldita.es that, as of today, there are no “good age verification tools available, and we may never have ones that respect our privacy.” In July 2025, it was announced that Spain will be one of the countries, along with Denmark, Greece, France, and Italy, to test the prototype application presented by the European Commission for age verification.

In the Spanish context there is already a set of laws that can protect minors in digital spaces, like the Organic Law on comprehensive protection of children and adolescents against violence, the Organic Law on the Legal Protection of Minors, and the Organic Law on the Protection of Personal Data and the Guarantee of Digital Rights. Regarding AI sexual generated content of minors, these cases can be prosecuted thanks to the expansion of the concept of child pornography (and the inclusion of virtual pornography, technical pornography and pseudo child pornography). But there are more initiatives in the way: the draft Organic Law for the Protection of Minors in Digital Environments was presented in Spain - currently in the state of being processed in Congress. The law seeks to criminalize the creation of AI generated sexual content of minors and to classify grooming as an aggravating circumstance in certain sexual offenses. The draft also seeks to establish new age verification requirements for platforms aimed at adults, raise the minimum age for the processing of personal data from 14 to 16, install free parental controls on all devices, and establish the penalty of restraining order in virtual environments.

In Romania, children’s rights in the online environment are the same as those they have offline. At the national level, these are regulated by Law 272/2004 on the protection and promotion of children’s rights, which includes clear provisions regarding online abuse. For example, Article 85 paragraph (1) specifies that minors have the right to be protected against any type of abuse and any form of violence, regardless of the environment they are in. Additionally, other regulations in the Criminal Code clearly criminalize certain acts, such as child pornography or sexual intercourse with a minor aged between 14 and 16. Since 2019, Law 221/2019 has also been in force, which prevents and combats bullying in schools, and it also contains clear definitions regarding cyberbullying in educational institutions, as well as identification tools and prevention measures.

Romania does not yet have a law to enforce age verification. A 2023 bill, the “Digital Age of Consent Law,” initiated by Liberal senator Nicoleta Pauliuc, proposes parental consent up to 16 for accessing online platforms, focusing on parental responsibility rather than technical checks. It also introduces obligations for social networks and gaming apps: filters against harmful content, child-safety standards, and bans on advertising to minors. Another initiative from the National Liberal Party targets children under 18 on Very Large Online Platforms (Snapchat, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, etc.), with stricter measures: verifiable age checks, customized parental control, bans on monetizing minors’ live content without parental consent, and fines of 0.5–3% of global turnover. Legislative consultant Bogdan Manolea warns these laws are hard to apply to global platforms without headquarters in Romania. He notes for Scena9 that children often bypass restrictions and that rights to privacy, free expression, and identity exploration must also be considered.

In Ukraine, digital content with sexual abuse of children is clearly a crime and is prosecuted under criminal law. At the same time, cyberbullying and some forms of psychological digital violence (humiliation, intimidation) are qualified only as administrative offenses. The Criminal Code of Ukraine explicitly refers to “child pornography,” which is defined as any image or video that simulates sexual abuse of a child or uses the image of a child. The law does not make an exception for artificially created content, so even if a child did not actually participate in the creation of the material, it can be classified as a crime. That is, if AI content realistically reproduces a child in a sexual context, it is equated with prohibited products, and the person who creates, stores or distributes such material will be liable.

Deepfakes and other kinds of AI generated sexual content are on the rise and they will definitely be one of the main challenges regulators will have to deal with from now on. In this collective quest for finding solutions, Denmark plans to change its copyright law and grant all Danish citizens copyright ownership over their own physical features (face, voice, body). This way, they hope to have legal control over AI generated content that uses their traits.

These are all solutions organisations and institutions have come up with in the face of an extremely complex and ever changing internet ecosystem of problems, broadly defined as digital violence. But they can only work partially, as long as the online environment knows no borders, is subjected to different sets of rules than those which govern offline societies, and is constantly shaped by phenomena never known before. The process of adaptation is slow and it involves lots of trials and errors, and the lack of transparency from giant tech companies and accountability complicates it even further, as consulted experts have expressed. It is essential that more and more people, organisations and institutions start acknowledging that digital literacy, cultural tools, technological infrastructure and coherent policies are not optional. They are absolutely necessary tools against the numerous forms of online violence that affect us all, starting from the earliest ages.

Editor for Scena9.ro: Andra Matzal

Editors for Maldita.es: Patricia Ruiz Guevara, Coral García Dorado

Editor for Rubryka.com: Viktoriia Hubareva

Main illustration: Malu Jaramillo for Maldita.es

This article is supported by Journalismfund Europe.