Around 500 people of all ages are sitting on benches, shoulder to shoulder, in the Elim Romanian Pentecostal Church, in North Phoenix, Arizona. It’s the evening service on the last Sunday of February. Today is Baptism day, so the church feels a lot more crowded than usual. Some of the women have their heads covered with scarves. Nobody wears masks. The followers direct their eyes to the evangelist Petru Lascău, who is preaching in their native Romanian. Pastor Lascău wears a black suit and a purple tie, and he gestures with his finger like a strict parent disciplining their child:

“I don’t know what kind of rebellion will one day take hold of our streets in this society that wants to cancel any sense of culture, right? We don’t know what color it will have, but it will knock at our doors, take us into the streets and set us on fire, as it did to thousands of buildings. We live in very difficult times, so don’t get attached to material things of this world.”

His sermon refers to the Black Lives Matter protests - perhaps the largest movement in U.S. history - that reached its peak momentum seven months prior. Shortly after Lascau’s sermon, eight youngsters dressed all in white step up on the stage, where they will be baptized. For Pentecostal Christians, baptism represents the most significant event of their spiritual journey. The baptism with the Holy Spirit is the first step for Pentecostals towards forging a personal relationship with Jesus Christ and an essential rite of passage in their journey towards salvation.

Alin Călini, the main pastor of the church, turns to one of the young Christians, a 17-year-old girl, whose dark hair falls over her white headband: “You’re making an oath with God today, through his son. For how long will you keep this oath?”

“For all of my life”, the girl replies in Romanian. She then crosses her hands in an “x” shape over her chest and falls back in the water basin, supported by two pastors.

A band of tubas, trombones, trumpets, French horns and drums plays a song that resembles a military parade. Baptisms are solemn affairs, so the church is silent.

Pastor and evangelist Petru Lascău is 70 years old and an influential figure of the Romanian-American conservative community in the US. Over 13.000 people follow him on Facebook, where he spreads his Republican views alongside Bible verses. “Yesterday we witnessed the funeral of the USA,” he wrote on January 20, under a photo of President Joe Biden delivering his Inauguration Day speech.

Lascău owns a publishing house - Lascău Scriptum - that has released over 20 books of essays and poems imbued with his religious and conservative views and which speak directly to his audience of compatriots. Certain works recount his life story during communist Romania, whereas other books address the difficulty of life as an immigrant or the dangers of liberal ideologies in the US.

“From familial relationships, to the church community, from the involvement of citizens in politics, to the evaluation of the information we’re presented in the media today, we always have to choose the good seeds from the bad ones, we have to go against the currents of time”, he writes in the description of his book Against the Current, published in 2019 and available on Amazon. “The corrupt society is affecting our families”, he writes in “At Sodom’s Gate”, which he describes as “a call for resistance against these harmful influences”. The book was published in February 2020 and its cover features the White House building lit in the LGBTQ flag colours.

There are about 85,000 ethnic Romanians in Arizona, many of whom fled the communist regime in their home country, which ended through the 1989 Revolution. Around 300 are part of the Elim Romanian Pentecostal Church, where Lascău’s preachings blur the lines between religion and politics in a community that is becoming a rising political force in the state.

Romanians for Trump

The first Romanians arrived in Arizona in the late 80s, a large number of them as political refugees. Like many Cubans who came to the U Sto escape the authoritarian regime of Fidel Castro, some Romanians are afraid that one day they will have a similar experience to what they lived back home during communism — persecution for expressing political and religious views, rationed food and electricity, and a lack of personal freedom. That’s mostly what leads a lot of them to embrace right-wing views. Even if he now lives in the land of freedom, Petru Lascău is afraid of what he calls “sexomarxism”, which he defines as an ideology imposed by American Democrats in order to normalize homosexuality and implement socialism.

At the insurrection in the U.S. Capitol on January 6, a giant Romanian flag with a hole in the middle – a symbol of the Romanian Revolution from 1989 – emerged from the crowds. “Trump Supporters think Biden is a commie so sometimes they’ll wave flags like this to act as if they’re fighting against communism”, a user explained on Reddit. That same day, outside of the Arizona State Capitol, two children were carrying a banner that read “Romanians for Trump.”

In the past 30 years, the Church has remained the institution that most Romanians living in the country trust. The Pentecostal church became one of the most important religious communities in Romania, being the fourth biggest, with over 400.000 followers. Nowadays, in the U.S.A there are around 30.000 Pentecostals of Romanian origins, in over 100 churches, according to pastor Cornel Avram, president of the Romanian Pentecostal Churches Union U.S.A and Canada (that Lascău is also part of). Pentecostals believe in a personal relationship with the Holy Spirit, to whom they speak in tongues, a practice in which people utter words or speech-like sounds. Pentecostal Christians also believe in miraculous healing, which they consider a divine gift.

Sociologist Gelu Duminică explains why Pentecostalism is so successful among Romanians. "Because God and his words become understandable to people, the pastor is a model, the message is transmitted using the familiar transmission channel for the receiver (music, parables of life, etc.), the promoted values are connected with events in community life, it’s a lot about the feeling of solidarity and empathy”. Moreover, says Duminică, “The Church responds to the existing needs / challenges at the community level, it offers the feeling that the person is listened to and heard. God is good and that becomes tangible through what happens, from the point of view of community relations.”

The formation of political beliefs

In the ‘80s, Lascău built the Betel Pentecostal Church in Oradea, which is still standing today. His pursuit led to systematic punishment by the communist regime, which didn’t endorse divine adoration of anyone other than the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu.

“I was fined 3.000 lei every day. My salary was 2.500 a month,” Lascău says on a Sunday morning, in the office of the main pastor of Elim church. Nevertheless, he continued to work on the church in Oradea, even after the fines amounted to 90.000 lei. For reference, the pastor mentions the cost of a Dacia car at the time: 75.000 lei. “We continued to work and then they sued us in court overnight.”

He refused to join the Communist Party, got demoted at work – from construction engineer to worker –and, in 1984, he sought political asylum in the United States.

“I applied for a passport to emigrate”. The Romanian authorities approved it. Back then, Lascău says, they weren’t jailing or torturing priests and pastors so openly anymore because of the influence they had on the masses. “They preferred to get rid of the undesirables, of those who had an influence on those around them.”

After being a pastor in Oregon and then in Chicago for 17 years, he was invited to preach at Elim, the oldest Romanian Pentecostal church in Arizona, built in 1980. (Currently, the largest Pentecostal church of Romanians in Arizona is Happy Valley, with almost 3,000 thousand members.) He has always preached in Romanian: “Pastor and poet, you can only be in your native language.”

Lascău says he supports the Republican Party because it promotes values that are compatible with his religious views. He is against abortion, against homosexuality and wary of “the New World Order,” referenced in the Book of Revelation. “There will come a leader as the savior of the world called the Antichrist,” he explains. “We voted for Trump because Trump not only shared these values that I talked about so far, but he opposed this rapid path towards a world government, towards globalism and the control of big corporations.”

Lascău compares the United States to a huge wheel that cannot move very fast. At the same time, he thinks that four years under President Biden “is still a pretty serious time for some fundamental changes that will be irreversible.”

And he is afraid.

“I am afraid that we will experience much more terrible times in America than the Soviet gulags or the dramas in China, when the Communists came to power,” he says. “I’m afraid of some of these dramatic changes, in the sense that Christians will start to be marginalized, persecuted. They block you on Facebook, everywhere. They intervene in church services, tomorrow - the day after tomorrow they ban the Sunday school of children who grow up and are educated through the Scriptures, in the name of health or in the name of who knows what else.”

Lascău is also afraid for Romania and his compatriots from all over the world. He is in close contact with neo-Protestant churches in the country and in the diaspora, where he is often invited to preach. During the pandemic, for example, he spoke online to the Romanian diaspora in Spain about the times of “spiritual confusion” in which we live. The pastor is also involved in campaigns to support the traditional family, one of the hottest topics for conservatives everywhere. Lascău says that he was personally not involved in Romania’s Family Referendum in 2018. (The vote asked citizens whether they agree to alter the constitution to restrict the definition of a family to one based on the marriage between a man and woman, in the context of sexual minorities facing widespread discrimination and having few rights.)

However, the Pentecostal Christian Church in Romania spoke out firmly in favor of the traditional family: “The Pentecostal Church will continue to defend Christian values, will insist that education remain untainted by progressive ideology, and [the Pentecostal Church] will continue to promote religious freedom and opinion.”

In 2016, Lascău gave a fiery speech at a protest of Romanians in front of the Norwegian Consulate in San Francisco against the Norwegian state’s decision to take custody of the children of Bodnariu family, who were accused of domestic violence. “Norway, do you want to protect our children from us, their parents? If you don't have children – because lately you have more distorted than natural families – why don’t you stop abortion in your own country? If you want children, why do you take away our children?”, Pastor Lascău shouted in defense of the Bodnariu family, also members of the Pentecostal church.

In a sermon in January this year, which was later posted on YouTube with the title “The Vaccine, the Sign of the Beast?” and gathered over 23,500 views, Lascău aims to answer his fellow Christians’ concerns regarding the vaccine against Covid19: “There is a tremendous fear about this vaccine.” He reads from the book of Revelation which describes the last days of humanity. As he comments on the verses, he builds on the fear already present in the Church: “People will die of plague, contagious diseases, pandemics, Covid and who knows what other diseases the followers of the coming Antichrist will invent and produce in their laboratories.”

Such ideological exchanges between the USA and Romania are not new. The Romanian pro-life movement is inspired by the US movement and often funded by American missionaries and organizations.

Homeschooling

One Friday morning, at 11:30, Samuel Leahu, a blond, blue-eyed 12-year-old boy, is sitting alone at a desk in a house where he lives with his parents and sister. On the table is a Bible and a book of Christian songs. He is focused on the TV screen, which is displaying a Bible study lesson that his mother put on a few minutes ago. An American teacher is teaching in English, in a class of about 15 students. Next to the classroom board that we can discern on Samuel’s TV is the American flag.

Samuel is in seventh grade and does homeschooling, like about 30 percent of the children who attend Elim Church, according to Samuel’s mother, Angelica Leahu. She explains that the main reasons she chose to educate her child at home is to protect him from “LGBT propaganda” as well as the lack of manners and of Christian values in American public schools.

The fear of reliving Communism

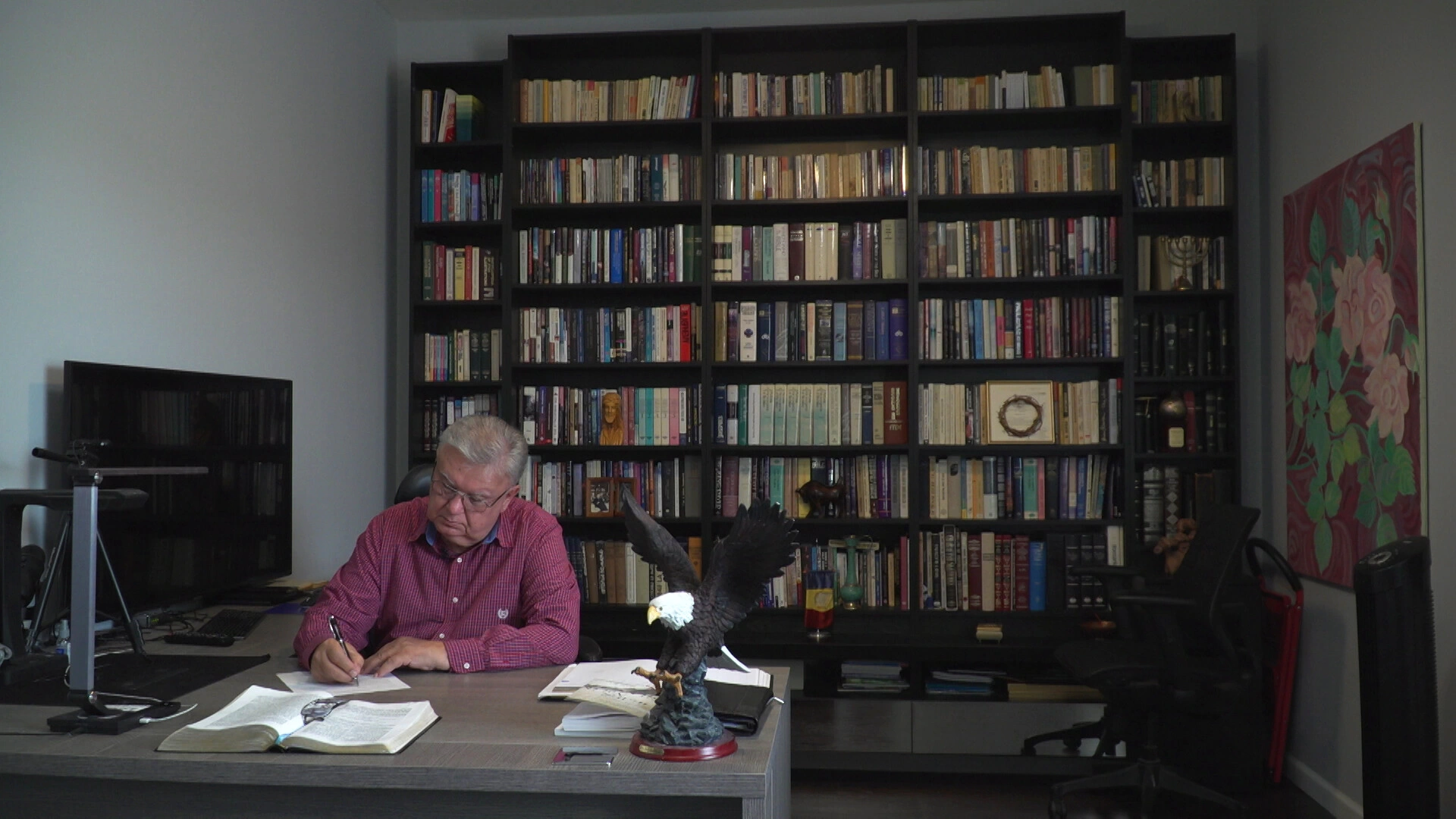

It's a chill March evening, and Lascau sits in his home office. One of the walls is covered by a bookcase with hundreds of books on religion, philosophy or literature, in Romanian and English. In addition to volumes by Liiceanu, Eliade or Noica, there are also titles such as “Blasphemy”, “Bait of Satan” and “Mideast Beast”. A Bible is open on Lascau’s desk ready to be read, as Lascau is in the habit of doing daily. Next to it is the statue of an eagle: “You have to be able to see things from above,” the pastor explains.

His oversized computer screensaver is a photo he took of a beach in Hawaii, one of his favorite places in the world. The other one is Romanian villages. He scrolls through his Facebook timeline and hovers over a recent post of his which features House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, alongside the message, “The mind of a liberal politician is open at both ends!” He claims that other similar “jokes” he posts every weekend - in a series he calls “the Saturday Smile” - were deleted from his page by the network algorithm. Such “censorship,” as he calls it, reminds him of the censorship he endured during the communist regime.

“And the pinnacle of irony would be that after I ran away from communism in Romania, where I suffered for 35 years - I left at the age of 35 - to return now, after 35 years of America, to communism.”

He also worries about President Biden’s push for gun control.

“If guns are taken from the Americans, we will become the slaves of the government, just like any other other country,” Lascău fears. “The Chinese don’t attack us because they know they’re dealing with 300 million people fully armed, and you can't fight that.” The United States is the country with the most weapons owned by civilians (390 million, which means 120.5 weapons per 100 inhabitants). In 2019 there were 14,400 gun-related homicides, and this year there were 293 mass shootings.

His wife, Rodica Lascău, sits on the couch and caresses their Yorkshire Terrier puppy, dressed in a purple sweater. Lascău plays a song on the computer composed by an artist from Romania, inspired by a poem written by him on homesickness. His eyes fill with tears.

Longing for Romania and the extreme right

“We are more Romanian than Romanians,” Alin Călini, the main pastor of Elim Church says, as he displays Romanian food from his fridge and freezer. Such goods soothe his longing for home. Călini is originally from Năsăud and settled in the U.S. 26 years ago, when he came with a family reunification visa, after his father fled Romania in ‘89 in search of the American dream. He studied theology and psychology at the postgraduate level and, in addition to his pastoral work at Elim - which he does voluntarily - he is a counselor for people who deal with drug and alcohol addiction. Together with his wife, he owns a nursing home for the elderly, a business that many Romanians in Arizona run.

Lidia Călini is a nurse and maths teacher at a secondary school. She came to America in the ‘80s with her parents and six brothers, Pentecostal Christians, after receiving an invitation from a Christian family in California. She met her future husband at Elim Church.

Alin Călini believes that politics is not a topic to be discussed from the pulpit of the church, but confesses that after the elections he could not refrain from denouncing those who voted for Biden during the sermon: “How can you call yourself a Christian and vote for someone who supports the immoral life of homosexuality and abortions?” he asked. “Trump is not the holiest man in the world either”, Pastor Călini says grinning, describing the Christians who took part in the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol as “two-cents brave men.”

However, the couple identify as far right, because they are conservative both “financially” and "morally.” “We are far-right and we are not popular. It is what it is,” says Lidia Călini.

Former undocumented immigrant, current Republican

On Passion Sunday, Mihaela Cuc, a 39-year-old Romanian woman from Iași, with long sleek hair, sits on a bench in the back of the church, close to the exit door. Her husband, Ciprian Cuc, 41, is sitting next to her, alongside their youngest daughter, who is 3 years old. Mihaela attends to her when she loses patience.

Mihaela has lived in the United States for 15 years and is studying to become a medical accountant. Ciprian has been here for 26 years and works as a data analyst. She speaks slowly and sometimes looks at him as if asking for approval; he sometimes completes her sentences.

They met at Elim Church 15 years ago and continue to come to church with their family. “If we experienced God in a Romanian church and had experiences with God in the Romanian church, I would also like our children to know God as we experienced him,” Mihaela says, sometimes with an American accent, sometimes with a Moldavian one.

“I think it’s also because we still identify as Romanians,” Ciprian adds.

Romanian-Americans share with other groups of immigrants a sense of belonging through church, which helps them reinvent their “sense of identity and communion after emigration,” researcher Johanna Richlin explains. In her study about Christian Brazilians in Washington DC, Richlin studies the “affective therapy” that immigrants find at church in the context of the loneliness and the longing they feel away from home.

Besides the sense of community it offers, Elim church is also a place where the Romanian-Pentecostal values are more alive than in American churches., the Cuc spouses believe. Their most important cherished values are “fear of God and a marriage without divorce,”values they would like their four children to embrace as well.

Ciprian voted for the Republican party, “like 95% of the church,” he says. They weren’t told directly by Lascău and the other pastors who to vote for, he says, but they were told to compare their Christian values with those of the presidential candidates. Besides the party’s positions against abortion and gay marriage, Ciprian says he also likes that the Republican Party “mostly encourages the working class to grow, to be entrepreneurs, to do things which can develop the economy. From what I’ve seen here, the Romanians in the US are hard working and do very good and beautiful things.”

He adds that living for 10 years under the Communist regime has shaped his political views. “Buying the basic things to have a good life was regimented – bread, flour, sugar, oil, gas. You couldn’t drive every Sunday – one Sunday they allowed the even numbers [of car plates], and the next one the odd numbers,”he recalls.

Ciprian Cuc thinks that the Democrat Party “wants to create a huge Government for everything to be controlled.”

Mihaela couldn’t vote in 2020 as she is not an American citizen yet, but she endorses her husband’s choice, even though the party opposes people like her. Fifteen years ago, she travelled from Europe to Mexico and was told by a smuggler to join a group of people from an orphanage who were traveling back to the United States — and that’s what she did. She recalls that nobody asked for her papers and thinks that “even today, in the car I was in, the person doesn’t know that I didn’t have documents.”

For that reason, even though she supports the other policies of the Republican Party, she is in solidarity with the migrants who are pursuing a better life and are caught at the border between Mexico and the U.S.A. She believes there should be avenues for the ones who don’t have criminal records to receive legal documentation. “You cannot understand unless you are in that situation.”

The first Romanian-American politician in Arizona

Ben Toma, his wife Ani, and their five daughters, have Sunday lunch in their house in Peoria, north of Phoenix. On the table there is chicken, potatoes and salad cooked by her and bread baked from scratch by him — a passion he developed during the pandemic. They just returned from Christ Bible Church, a nondenominational American church which they attend weekly and where they are in charge of the musical program. Ben Toma plays the keyboard and sings, joined by two of his teenage daughters.

Before going to this particular church, Toma’s family attended Elim for seven years. In 2006, they left because they felt the church was much too conservative. Toma and his wife say they have tried to “modernize” it. Lascău supported their youth camps and other ideas they tried to implement, such as more approachable preaching connected to daily life. The leadership of the church resisted change. “Elim is a dying church”, one of the Toma girls blurts out spontaneously at the table, before putting food on her plate. Her sisters giggle and her parents reprimand her for being too straightforward.

In 2016, Ben Toma became the first Romanian-American in the history of Arizona to be elected as a public official. He is the leader of the Republican majority in the House of Representatives and represents the 22nd legislative district, located in the Maricopa district, with a population of 240,808 people.

Talking immigration inside the Republican Party

One Monday morning, in his office in the Phoenix Capitol building, Toma says that Romanians in Arizona are not a cohesive and united community, and are distrustful of politicians. It's understandable, he thinks.

Toma came to the United States in the 80’s, when he was nine, after his parents escaped Ceaușescu’s regime, and he still remembers some of the absurdities that people would need to do for those in power. He claims that, before Ceaușescu visited their town, Șăulia, people painted the grass green and hung fake apples in the trees, even if it wasn’t summer yet, so Ceaușescu would feel satisfied by his country’s prosperity.

The politician was recently invited by the former Romanian ambassador to the United States, George Maior, and former head of the Romanian Intelligence Services, to visit Romania and discuss politics. He plans to visit his home country at the end of August accompanied by his Republican Party colleague Russell Bowers, the Speaker of the Arizona House of Representatives. “I am not sure yet who we will meet, but probably who the Embassy thinks we need to know. And possibly, the new ambassador [n.r. Andrei Moraru was proposed ambassador in February], if he will be available”. Toma says he does not have connections with the Alliance for the Union of Romanians [a far right populist party] and does not follow the party closely. “I focused on the work we do here, including the largest tax cut in Arizona's history (...), so I didn't get involved in Romanian politics at all. I care about my country and I wish it well, maybe I can help from here in the future.”

In February, both Toma and Bowers voted for a bill that would grant religious services essential services status, in order to secure their functioning during pandemic closures. However, when it comes to immigration policies, the two do not completely agree.

On Toma’s desk in the House of Representatives there are a few flags, including the ones of his native and adoptive countries, Romania and the U.S.A. Above his desk, Toma framed a Ronald Reagan quote, “America is too big for small dreams”. Bowers sits opposite Toma and their ties have similar patterns – white, oblique lines - as if they had planned to be in sync.

“We have to find a way to be more welcoming towards immigrants in particular, as a party,” Toma says.

“I want more immigrants from Romania,” Bowers says sarcastically. “I don’t know if we have an immigration problem, I think we have a welfare problem. That we are now in the mode of just giving it away – If you can get here it’s all free, and that’s the wrong message,” Bowers adds.

God and politics

One spring evening, pastor Petru Lascău is at home, recalling a moment when a colleague, pastor at an American church, asked him for whom he preaches.

“For Romanians,” Lascău answered. He remembers his colleague correcting him: “Listen, we preach the gospel for the white man, between the ages of 20 to 45. Because he is the most discriminated person in America. If you are Black you don’t have any problem, if you are Mexican again you don’t have any problems, but if you are white you are discriminated against.”

Both Lascău and his wife strongly agree with this statement.

“We are a political and religious animal at the same time,” he says when we ask him why he doesn’t separate religion and politics. “We are not allowed to choose one over the other – if we do so, we are wrong.”

He then quotes Charles Spurgeon, an English Baptist preacher, whom he calls “the prince of preachers.” “Take the Bible and the newspaper in your hand and read them both, but interpret the newspaper through the Bible, always interpret politics through religion.” That, Lascău says, is a rule he’s always followed.

*

This story is part of an extensive documentation project of the conservative Romanian community in the U.S.A, which will take the shape of a documentary film.

PHOTO main: Ben Toma, the first Romanian-American politician in Arizona, before a meeting in the House of Representatives, in the Phoenix Capitol building.