After the disputed elections of October 2024 and the ruling party’s decision to freeze Georgia’s EU accession process, Tbilisi took to the streets. After the wave of protests came the repressions: hundreds of young people were arrested, opposition members ended up behind bars, and journalist Mzia Amaghlobeli became a symbol of resistance beyond the country’s borders. Among the hundreds of people detained at the protests, 48 ended up on trial. Civil society, those who took to the streets and continue to go out, call those arrested prisoners of conscience, while the court considers them vandals.

Update: October 6. On October 4, local elections were held in Georgia, with Georgian Dream winning over 80% of the votes, after six of the eight opposition parties boycotted the vote.

That same day, tens of thousands of people protested in Tbilisi. Some of the demonstrations were organized by the opposition, while others gathered on their own initiative, as they have been doing for more than 300 days.

In the evening, a group of protesters attempted to enter the Presidential Palace but were dispersed with tear gas and water cannons. Many believe the incident was staged to discredit the peaceful protest. Following the arrest of the protest organizers and threats of further reprisals, people returned the next day to Rustaveli Avenue, showing that the movement continues despite intimidation.

It is the end of August, past seven in the evening, and people begin to gather in the square behind the Parliament in Tbilisi. There are few at first, mostly journalists and some activists. A few minutes later, from the right side of the building, comes a column of dozens of people heading noisily toward the square. Most of those in the column are over 50 – smiling, loud women and men, some with their children and grandchildren. The journalists greet them with warm embraces, as if welcoming a procession of guests to a celebration.

Several young people light smoke flares as a group of about 12 people, mostly women, stand face to face with the police, the crowd gathered behind them. They hold a long banner that reads ‘Georgia belongs to the people.’ A few wear T-shirts printed with black-and-white photos of young men—each shirt showing a different face. They are parents, carrying on their chest the image of their arrested son, one of more than 40 detained after the protests for the European path.

In an attempt to find out more about those arrested and their families, I spoke with two of the mothers. That is how I learned how a few young men forged friendships on the defendants’ bench, and how their mothers found a family in each other.

After the parliamentary elections of October 27, 2024, in which the ruling party “Georgian Dream” claimed over 50% of the votes amid accusations of fraud, Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze announced that Georgia would stop EU accession negotiations and would refuse European grants for the next three years. The statement triggered a wave of massive protests, during which police used tear gas and water cannons, while the crowd retaliated with fireworks launched at the police.

Since then, at least 48 people have been detained on criminal charges in connection with the pro-EU and anti–“Georgian Dream” protests. Numerous detainees reported beatings and inhuman treatment; the Ombudsman’s report shows that 60% of the 442 detainees visited between November 28, 2024 and March 1, 2025 declared that they had been abused. According to the Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association (GYLA) and a joint statement by over ten Georgian NGOs, detainees were assaulted by police during detention and afterwards: in vans, at least six special forces officers beat them in turn. At the order of their superior, they hit them in the liver and back of the head, spat on them, insulted them, and threatened them with rape. In addition, dozens of other people, including journalists, were attacked by violent groups allegedly close to the ruling party. Despite the numerous abuses documented during the dispersals, not a single police officer has been held accountable so far.

“I didn’t know he was that strong. In the end, we don’t know our children, we just think we do.”

On the evening of December 4, 2024, during a routine scroll through social networks, already a habit after the previous day’s protest, I found my feed full of posts with the same name and the same face. A handsome young man with a gentle gaze, appearing in different images: on the theater stage, in film scenes, and in commercials. It was the first time I had heard of Andro Chichinadze, even though I follow almost all the news in Georgian cinema. In a single day, the regime’s repression of protesters took on a new turn, marked by a special guest star: one of the most beloved actors of the new generation had been detained by police, accused of participating in group violence – a crime punishable by four to six years in prison.

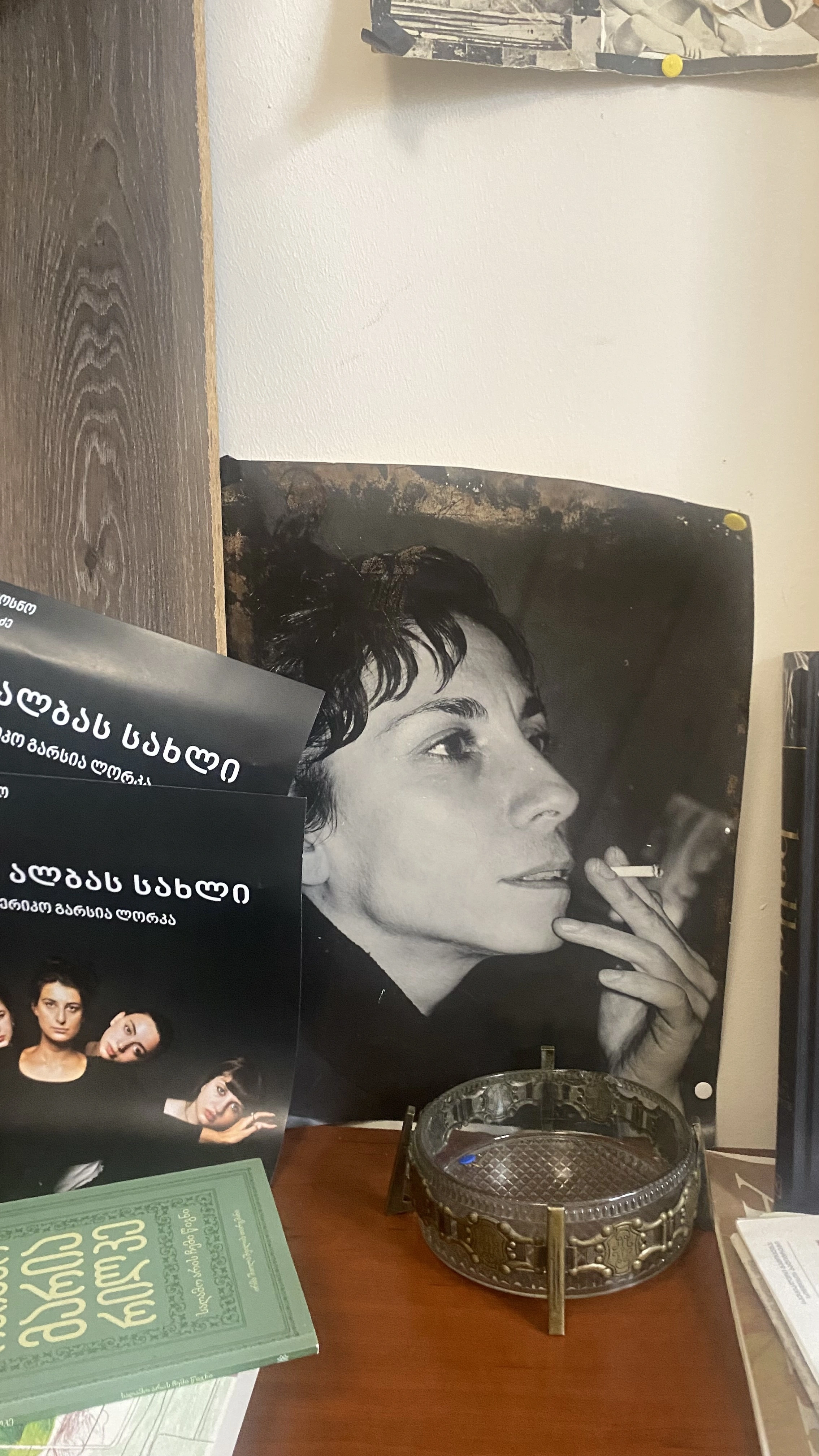

It is the last days of August, but summer still rules the city in full force. I meet Andro’s mother almost nine months after his arrest, about the time you would carry a child in your womb. Lika Gunchadze, a petite woman with a short boyish haircut and the grace of a dancer, greets me in front of the building where she lives with her husband Otar, two dogs, and their son. “After his divorce, Andro showed up at our door with his luggage in hand… should I say I was happy?” she tells me, with an ironic smile. We climb the stairs, and as soon as we enter the door, a big black stray dog greets us. “His name is Django, Andro named him when he took him from the shelter. In our home, the rule is simple: all our dogs are taken from shelters or from the street.”

I step into a spacious, slightly dark apartment, with old furniture and portraits on the walls. Lika sits on the couch, Django close behind, never leaving her side during our conversation. On the table lie cigarettes and an ashtray – “here we smoke inside”

A former ballerina, Lika now has her own studio where she teaches ballet, plastic movement, and dramatic art. Her low voice reveals the actress within her. Her husband Otar, Andro’s father, is a doctor. “Otar’s grandfather was shot by [the Soviet regime] in ’37. We have been antisoviet all our lives, in this sense Andro had an example.”

On April 9, 1989, in Tbilisi, Soviet troops violently dispersed a peaceful protest on Rustaveli Avenue, leaving 21 dead, most of them women, and hundreds injured.

In her youth, Lika never missed a protest. She was present at the Rustaveli demonstrations of April 9, 1989. Today, the street to the right of Parliament bears the name of that bloody day. Ironically, it is right there that the first violent clashes between police and protesters usually take place. In recent years, her activism had moved to Facebook, but Andro’s arrest in December 2024 brought her back into the streets.

Although he grew up in an artistic environment, his parents did not expect Andro to choose this path. Shy by nature, he surprised everyone when he announced he would study acting. At 29, he already has several feature films behind him, including co-productions, some series, commercials, and music videos. For some time he had rediscovered his passion for theater, joining the troupe of the Vaso Abashidze New State Theater. Lately he was preparing a very personal project – a documentary about climbing seven mountain peaks around the world, as a metaphor for his journey toward healing.

“After a concussion on set, Andro began to experience derealization and depersonalization. He got treatment, climbed a mountain, and decided to turn his experience into a project to help others,” his mother says.

On the day of her son’s arrest, December 5, Lika was not home. Her husband called to say they had come for Andro, but by the time she arrived, he was already being led in handcuffs to the car “The whole courtyard was full of men in uniforms. I shouted at them, but he calmly told me: ‘Mom, calm down.’ Later I found out that he had told the police: ‘Come on, just get me out of here before my mum comes. You don’t want that, trust me.”

Like other detainees, Andro was accused of throwing a bottle at police during the pro-EU protests. According to his mother, his lawyers, and many activists, Andro was chosen as an example for all young people: “If we can do this to him, imagine what we could do to you.” In addition, the arrest could also be a revenge, a threat against Elene Khoshtaria, leader of the Georgian opposition party Droa and Andro’s cousin. (On September 15 this year, Elene was also detained, for vandalizing the campaign banner of Tbilisi Mayor Kakha Kaladze, member of the “Georgian Dream” party, candidate for a third term in the local elections of October 4, 2025.)

Lika tells me how, on the same couch where we are now sitting, she used to wait at night for Andro to return from filming or rehearsals. She tells me how close they are. Since he was a kid, they shared the ritual of watching movies together. Even now, they do their best to send him USB sticks with Cannes films, new Georgian productions, everything he hasn’t yet managed to see. Yet, she confesses that this experience made her rediscover him – there are still things about her son that surprise her. At one point, Andro was offered release if he would apologize. The young man refused, adding that he would not even submit a request for pardon. “I didn’t know he was that strong. In the end, we don’t really know our children, we just think we do.”

For nearly nine months, ever since Andro’s arrest, mother and son have stayed connected mainly through letters and phone calls. Andro chose to replace visits with phone minutes. “I write him very, very long letters. That’s what he asked me. He doesn’t like to write, but on the phone he talks a lot. The last time they spoke, he was excited to have discovered [the Russian writer Varlam] Shalamov. Each time we send him a new package of books.”

Like many other parents of those arrested after the protests, Lika was surprised by the wave of solidarity across the country: “I had read about this in books, seen it in films, but I never imagined I would live it. Andrusha’s friends have become my friends.” Sometimes taxi drivers refuse to take her money, or shopkeepers shout after her “Tavisupleba, Andro!” (Freedom, Andro!). Andro’s colleagues hung a large banner with his image on the facade of the theater where he performed; meanwhile, the director, actively involved in the protests, was dismissed for “failure to fulfill the theater’s fundamental purposes.” Every week, Andro’s friends come to visit Lika and her husband, often straight from the protests. On her birthday, September 8, she insisted I stay a little longer to meet those she calls “the force of the protest.” They had come directly from a demonstration in front of Mayor Kakha Kaladze’s campaign headquarters. Solidarity with Andro has also crossed Georgia’s borders. In May, the European Film Academy admitted him as a member. Patch Adams, the first hospital clown and founder of the so-called therapeutic practice of hospital clowning, sent Andro a long letter expressing support and solidarity for him as the initiator of the practice in Georgia.

There were also attempts by pro-government media to discredit the young actor, suggesting he would be ready to abandon his values for professional purposes. In 2021, before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Andro appeared in a video of Russian rapper Basta and in the film Nina, by Russian director Oksana Bychkova. But the plan to “unmask” him partially failed when the director recounted how she met Andro and what he asked her before accepting the role: at the audition, he wanted to know her position on Putin. Only after Bychkova told him that she had never supported him or his regime did Andro accept the role.

Before leaving, Lika takes me on a tour of the house and tells me about the old furniture with carved wooden angels, passed down from her forebears, about the portrait of Andro’s grandfather, whom he strongly resembles, and about her husband’s passion for flowers, which have now all moved into their son’s room. It is a small one, with a pile of books on the table waiting their turn to be passed on, souvenirs from different countries, and family photos. On the wall, next to a large unframed mirror, hangs a big poster of Andro climbing mountains. The unfinished documentary.

“I lost many people after Irakli’s arrest, but I gained even more”

At the end of January, I left Georgia for Chișinău, planning to stay three months but it turned into five and a half. All this time, in my fumbling attempts to live hic et nunc, I tried to follow the events in Georgia a little less. I knew anyway that most of the opposition had ended up behind bars, that independent journalist Mzia Amaghlobeli had gone on hunger strike, and that nearly 50 protesters, most of them young, were facing prison.

In mid-March, once again my feed was flooded with the same reel: a young man, basically a teen, with an adorable name and a smile that makes you blush, sitting on the defendants’ bench in a courtroom, proposing to his girlfriend. His “bench mates” embrace him, and the room bursts into applause. The young man is Irakli Miminoshvili, a first-year student, detained on December 4, under the same accusation as Andro Chichinadze – “participation in group violence.”

A week after my encounter with Lika, I meet Irakli’s mother, Elene Khundadze. We agree to see each other near Tavisupleba (Freedom) metro station, a few steps from Parliament. I recognize her as soon as she approaches – Irakli looks strikingly like her. That’s the first thing I say. She smiles and adds that her daughter, Liza, looks exactly like her too. Tall, with eyes shadowed by heavy dark circles, she holds her phone in her hand. On the screen is a photo of her son.

We sit down in a café on the terrace of a mall. Elene smokes, so our conversation begins over a cigarette. My eyes catch her massive bracelet and rings. She notices and shows me her other hand – a simple blue braided bracelet. “Irakli made us all bracelets in prison. He learned it there.”

For the past 10 years, Irakli and his sister have been raised only by their mother, after their father passed away. They rent a house with a shared yard. Though he resembles them physically, his character is entirely different—hyperactive, overly cheerful, almost childlike. As a teenager, he began earning his own money, sometimes doing deliveries, sometimes working in kitchens, his great passion. He would welcome his mother home from work with elaborate dishes, carefully decorated with little flowers.” “When he worked in restaurants he had to wake up at five, but he couldn’t, so I woke him up. At some point I told him: I’ll give you the money, just spare me this waking up before sunrise. Anyway, he kept going.”

His dream was to study at the Culinary Academy, but that education did not grant exemption from the army, so he chose the Faculty of Management instead. He paid for his own studies, though he managed only two months of them. Sometimes their mother would also join them, but only for a few hours; the teens stayed until morning. “I begged them to stay home just once, so I could sleep peacefully for a night. But no. I’d go to work, they’d come back home. I’d come back, and they’d already be gone again. The only thing that calmed me was thinking he had a girl he was seeing… he kept saying he’d introduce her to me.”

On December 2, 2024, Irakli returned with swollen hand and leg, having been hit by tear gas canisters. That was when he told his mother he’d had a bad dream and wondered if it might be better to leave the country. “I felt uneasy,” she recalls, “but I reassured him: if something happens, we’ll find a way to pay the administrative fine.” The next day, Elene spotted a suspicious car parked in front of the house—a Skoda packed with men in civilian clothes. “At four in the morning, he called me: he’d run from the police through the back alleys and was asking me for taxi money.”

On December 4, although angry after another sleepless night, Elene kissed her son and went to work. That afternoon, 20 people in four cars came to arrest Irakli.

Elene didn’t get to see him. Only Liza was home, and she told her how it all happened. “From what she said, Irakli seemed in control of the situation. He joked and dragged things out to give the lawyer time to arrive: I want water. Not from this glass, another one. These shoes aren’t right, I need different ones, and so on.”

What followed she remembers vaguely, as Liza handled all the questions. The police confiscated their phones and computers, leaving only a sheet with the charges against her son. Soon, relatives and friends who had learned of the arrest from the news began to contact them. Many mentioned the same video, which had been circulating on social media for several days, showing a young man, later presented as Irakli, throwing an object at police. “That’s when I understood why he suddenly brought up leaving the country…”

The next day they brought him cigarettes and food, but Elene didn’t see him until the first court hearing, in January 2025. “When they escorted all eight of them out of the room, I stood on a chair just to see him a little longer, as he passed by the window.”

It is past 7 in the evening and we head toward Parliament, where another protest in support of those arrested is about to take place. We stop at an ice cream kiosk. On the way out, a man starts talking to Elene, holding her for several minutes at the door.

"Do you know each other?" I ask when we leave.

"No, no, first time I see him. He recognized me as Irakli’s mother and asked if I’m going to the protest."

"Does that happen often?"

"Very often. On transport, in the grocery store, on the street. Strangers hug me or say a few kind words. I lost many people after Irakli’s arrest, but I gained even more."

On September 15, 2025, Irakli turned 20. Close to midnight, Elene, Liza, Irakli’s new wife, friends and supporters went to Gldani prison with a cake, candles, and flares. In a video published online, about fifteen people can be seen singing ‘Happy Birthday’ and shouting through a megaphone: ‘Happy birthday, Ika!’ ‘Freedom!’ Their eyes are lifted upward. From afar, behind the barred window, a dark silhouette, barely visible, answers back: ‘Freedom!

On September 2, 2025, Tbilisi City Court judge Tamar Mchedlishvili reclassified the charges and found Irakli Miminoshvili and seven other participants in the pro-European protests guilty under Article 226 of the Criminal Code – “Organizing group actions that disturb public order or active participation in them.” Irakli and four other defendants were sentenced as “group members” to two years in prison, while three others, judged as organizers, received two years and six months.

On September 3, 2025, Andro Chichinadze and another 10 defendants received the same sentence of two years in prison, after the reclassification of charges.

All of the detainees pleaded not guilty. During the trial, it was not proven that there had been any connection between them, although this is a mandatory condition to speak of “group violence.” Even the police officers who testified were unable to identify who exactly had injured them during the protests.

When I met with Elene, we also spoke a little about Lika, about the friendship that had grown between them. That is when I learned that for some time Andro and Irakli had been sharing the same cell. Now Andro can no longer read in peace because Irakli’s hyperactivity drives him crazy. He jumps around, teases him. On the other hand, Andro pushes him to read at least a little and says he’ll get him a part in a movie. After one of the hearings, Irakli’s mother asked Andro what she should tell Lika to bring him. Andro replied: “I don’t need anything, I eat very well; Irakli cooks something every day. When I left, he was just starting to make dumplings for me.”

In these nine months, the parents of those arrested, mostly mothers, sisters, and grandmothers, have turned into a real extended family. Marina Terishvili lost her first son on April 9, and saw her second, a taxi driver over 50, arrested at protests. Keti Kerashvili fights for her brother Irakli, a plastic surgeon. Nargiz Davidadze, inseparable from her husband Zurab, attends every demonstration in the name of Zviad, leader of the Dafioni youth movement. Nani Tsuluia, always with a smile, chants for her son Giorgi, a medical student.

And many others.

Together they go to protests, hand out leaflets and newspapers across different regions of Georgia with their sons’ letters, attended the trials of each other’s sons, talk daily on their WhatsApp chat, and sometimes gather at Lika’s summer house. At protests, I watch them embrace when one cries, laugh freely, and march side by side at the front despite heavy rain and fines. I look at them and they seem like old friends who once shared the same dorm room. Perhaps it’s the pain they share. And perhaps, just a little, it’s because they are women.